A strange sense of amnesia sets in when we lose all sense of a place.

First, we memorialize; then, we misremember; and finally, we forget. Without storytellers to carry forward our history, our culture and community is eventually lost.

Fortunately, some histories are kept alive in the stories of those who lived there, worked there, played there and loved there. Even 25 years after a catastrophic fire ravaged the Hotel Washington, the landmark is still alive in the hearts and souls of everyone who knew it. At the same time, an entire generation of LGBTQ Madisonians has grown up hearing facts, fictions, and folklore about a place they will never know themselves.

And that’s really a bit tragic.

The day it all went down

Shortly before sunrise on Sunday, February 18, 1996, hotel manager Michelle Dorland and bar manager Steve Richards were playing cribbage after-hours in Rod’s. Normally, they’d be gone by 4:30 a.m., but on this particular night, they lingered later than usual. To this day, Hotel Washington tenants are grateful that they did.

At 6:15 a.m., they heard an ominous sound: a fire alarm had registered within the building.

Café Palms was on fire.

Dorland and Richards ran upstairs to the first-floor restaurant, where they met Jeff Schultz, assistant manager and hotel resident, who had called the fire department. The Café Palms kitchen was filled with smoke, so they didn’t immediately see the flames halfway up the office wall. The office sat above a basement furnace room, so it seemed the fire might have started in the basement and come up the wall.

Firefighters arrived around 6:15 a.m. Schultz, Dorland, and Richards were on the third floor, banging on doors and ordering all 15 tenants to get out. False alarms weren’t uncommon at the Hotel Washington, so few people left the building when the alarm went off. Fifteen minutes later, the smoke was so thick that people could barely see. Half-asleep, half-awake, and half-dressed, residents poured into the parking lot in a daze. By the end of the evacuation, Dorland and Richards were crawling on all fours through pitch-black hallways, relying on memory and instinct to find their way out.

“I was choking on the smoke,” Richards told the Wisconsin State Journal that day. “I tried to grab a fire extinguisher, but it was already out of control, and my response was to just get people out.”

Additional firefighters showed up at 6:28 a.m. Eventually, 12 firetrucks and 42 firefighters would battle the blaze. By 8:00 a.m., large crowds had gathered to watch in shock and disbelief as the violent, fast-raging fire devastated the building. Shortly thereafter, the Speed Print shop exploded in flame, as the fire reached its flammable chemicals. Most of the building collapsed, leaving only one jagged brick wall and the door to Café Palms, surrounded by a charred pile of ice-glazed rubble. Many LGBTQ people stood sobbing and hugging as they watched their refuge burn to the ground. People reported seeing the smoke from as far away as I-90.

The timing was especially poignant. The Capital Times had just featured the Hotel Washington in an ongoing series of Rhythm articles celebrating its history, heritage, diversity, and community. Suspicious fires were not unknown to Madison. A suspicious 1982 fire destroyed nearby lesbian landmark Lysistrata (319 Gorham St.). The Rodney Scheel House was torched only eight months prior. Even the hotel had recently burned, when a 1995 NewBar fire damaged the second and third floors.

Schultz, Dorland, and Richards remarkably survived their ordeal without serious injuries. Fortunately, no human lives were lost in the blaze, but employees would later recall two resident pets—a kitten and a tarantula—did not make it out alive.

During the fire, Hotel Washington co-owner Greg Scheel saw a silver cross shining through a gaping hole in the bricks. “I never even knew that was there. There was so much beauty and mystery in that building.”

It was a moment of inspiration. Scheel immediately announced plans to rebuild on the site. This was exactly what Madison needed and wanted to hear in the moment. Even in this darkest hour, Greg Scheel and his sister Sherry Nelson kept the city focused on a brighter future.

“There are too many people counting on us to come back,” he said.

The fire was still smoldering the next day, as over 500 gathered outside the Wisconsin State Capitol for a mournful vigil. Three hundred gathered for a memorial service Sunday at the train depot next door, overlooking the smoking mass of memories.

“The fire has taken a lot from a lot of people,” said drag artist Racine, “but this complex gave everything to us, and we will rebuild.”

On Day 3, photographers captured the now-iconic photo of a rainbow pride flag hanging over the destroyed hotel. By March 6, all that remained was the concrete front steps.

“We all told ourselves, it won’t be that bad,” said Toni Ziemer, Club De Wash employee. ”But once the smoke cleared, and we saw how bad it was, we knew it was going to be torn down. It was really devastating.”

“It can’t believe it’s gone,” said Michelle Dorland. “It provided a safe haven for a lot of people, and it’s going to be missed.”

“It’s like a funeral, and we’ve lost a friend,” said Mike Verveer, Alderman for the 4th District.

Losing LGBTQ Madison’s heart

The Hotel Washington was more than just a 22-room residential hotel. It was an elaborate and intentional collective of high-concept businesses, including:

- Barber’s Closet, a gorgeous Prohibition Era speakeasy only accessible through a secret entryway, where goldfish bowl-sized cocktails, tarot card readings, and murder mystery events were on the menu;

- Rod’s, an old-school, unapologetic, aggressively masculine gay bar in the basement;

- Club De Wash, an intimate concert venue that offered live music almost every night for 19 years, hosted an astonishing list of up-and-coming artists over the years, including Smashing Pumpkins, Soul Asylum, Babes in Toyland, Alanis Morrisette, Bush, Sarah McLachlan and Dave Matthews Band;

- NewBar, an ‘80s-style video bar featuring DJs, drag shows, and a dance floor to die for;

- Café Palms & Café Espresso, a higher-end, late-night hotspot open until 3:30 a.m. and its lower-end coffeehouse neighbor, usually crammed with UW students;

- Microbar, a small tap offering over 75 rare microbrews, long before they were widely available;

- Speed Print, a copy shop; and

- Barber’s Closet Salon, a popular, two-seat hair salon.

The fire claimed not just these places, but everything that gave them their unique sense of place. Club De Wash lost hundreds of musician photos that once decorated its walls. NewBar’s resident DJ lost over 800 albums, some of which could never be replaced. Historic photos that once covered the walls of Café Palms were also destroyed.

Fortunately, some artifacts escaped the fire. Rodney Scheel’s desk. The legendary Rolodex of Barber’s Closet drink recipes. Amazingly, ALL of Greg Scheel’s videos, which now populate the Hotel Washington YouTube channel. Hundreds of photos, which were rescued, hung on clotheslines to dry, and carefully restored by volunteers over the course of four days. (Greg later scanned these photos and added them to the Hotel Washington Memories Facebook group, founded by Toni Ziemer in 2016.)

More than 100 people lost their jobs, but in spirit, they lost far more than employment.

“It was a lot more than just a job for me,” said Richard. “It was an integral part of who I am.”

“This place was the best place I ever worked in my life,” said Mike Sharpe of Club De Wash, “Everyone was so cool. Everyone was in touch with each other. We worked as a unit. It hurt me really bad to see the walls falling down. The place was an institution. It was a place where anyone in the country could come and feel comfortable in one unit or another.”

“I worked at the Barber’s Closet and the New Bar,” said a bartender. “I’ve never felt more like I had a family than when I was there. I’m not ready to let go.”

“That place had a lot of character and I wonder where the ghosts will go now,” musician Marques Bovre (1962–2013) told the Wisconsin State Journal. “When old houses burn down, they say the ghosts have to find a new place to live.”

“We’ll come back 100 percent bigger and better,” said Lori Sandy, Club De Wash manager. “The people who came here and worked here share a sense of community and we will bring Club De Wash back.”

Burning questions

A Madison Fire Department spokeswoman said that arson had not yet been ruled out. Division Chief William Olson said, “We have to start digging—we have to dig to find the point of origins and the cause.”

Greg Scheel disagreed. “There’s not any inkling it was arson,” he said. He said most of the $2 million in damages would be covered by insurance. He also dismissed speculation that anti-gay fireman Ron Greer had somehow caused the fire.

Nikki Baumblatt, co-producer of a popular LGBT radio program on WTSO-AM, wasn’t so convinced. “The fire is a reminder that Madison isn’t as progressive as some people think. Greer may not have started the fire, but he ignited the flame of anti-gay sentiments in Madison.”

In response, Greer simply said, “I am not sorry that some of these businesses are gone now, but I am sorry about the fire.”

The Keanu Reeves/Morgan Freeman movie Chain Reaction was supposed to be filmed outside the Hotel Washington. Although scenes within the state capitol building were retained, planned scenes at the train depot were scrapped.

In the end, the fire was traced to a simple, routine, and innocent action. An employee had dumped an ashtray full of cigarette butts into a trash can, as they’d probably done hundreds of nights before then. On this particular night, the embers somehow sparked an inferno that engulfed the bar.

“The Wisconsin Light wishes to express its heartfelt sorrow and deep sense of loss to the Scheel family and the entire Madison LGBT community at the loss of the Hotel Washington,” wrote the editors of the state’s leading LGBTQ publication in February, 1996.

“We remember fondly all the good times we had there and the people that we met. We remember the laughter, rare nowadays. We remember the cruising. We remember the fun. We remember sitting now and again and talking to Rod. We’d talk about AIDS. We’d talk about politics. But most of all, we’d talk about things that gay men do. Now we have our memories of an open, friendly place, where we could be accepted and not feel afraid. But we are persuaded that the Hotel Washington will rise again.”

Everyone was.

How the Hotel Washington happened

The Hotel Washington traced back to 1885, when the Commercial House (also known as the Madison House) operated a display headquarters, sample room, and lodging on West Washington Avenue for traveling businessmen. Over 20 trains arrived daily—from Chicago, Milwaukee and Minneapolis—at the Milwaukee Road depot next door.

In 1904, E.G. Trumpf acquired and rechristened the “Trumpf Hotel” as the finest accommodations available in the city. After a shocking 1906 fire, Trumpf converted the wooden hotel to “fireproof” brick. Ten years later, he sold it to August Harbort who renamed it the Hotel Washington in 1916.

The hotel changed hands many, many times by 1961, when Louis Wagner became owner. Wagner was the operator of Koin Kafe, a trendy automat in the Park Hotel on the Square, but not financially prepared to preserve or modernize the Hotel Washington. When the Milwaukee Road Depot closed in 1969, the hotel transitioned from a one-star traveler’s hotel to 60 low-income housing units.

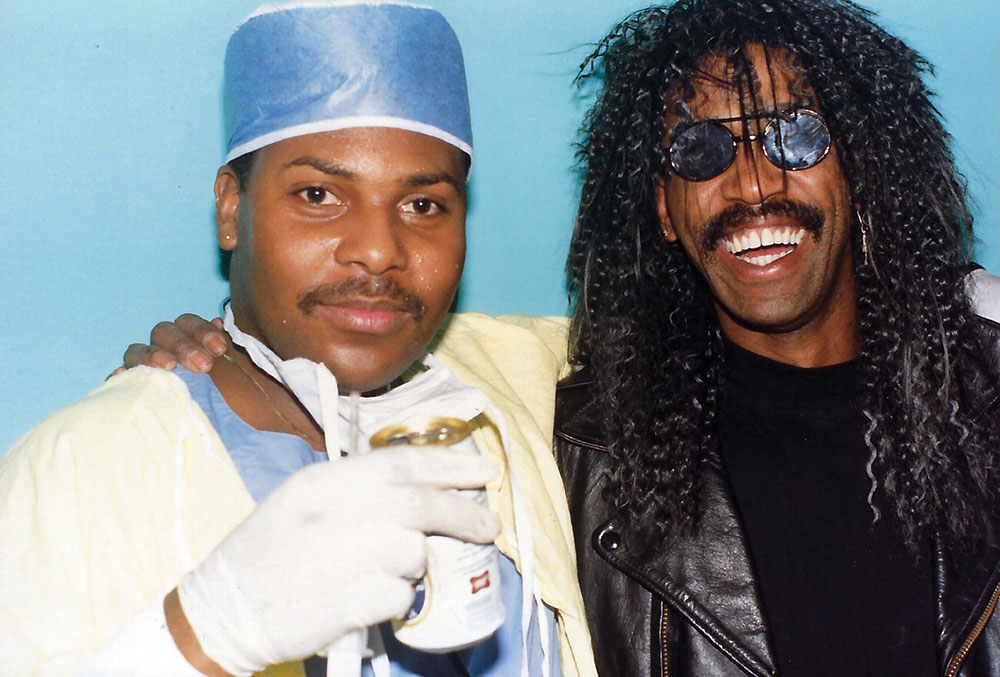

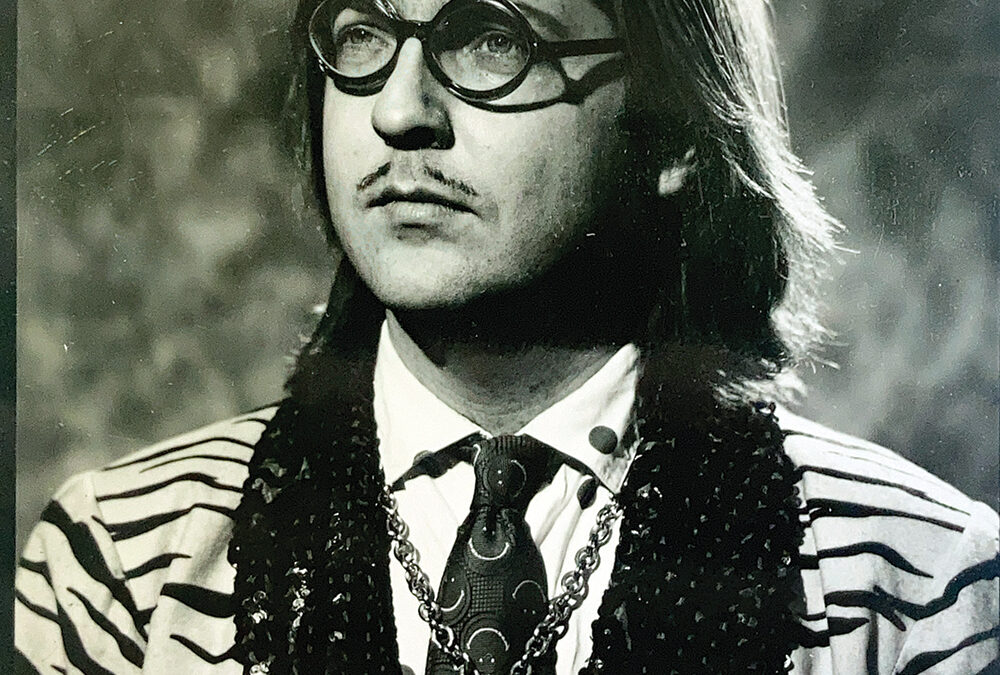

Rodney Scheel opened the Back Door (46 N. Park St.) as Madison’s first out-and-proud gay bar in 1972. For safety reasons, customers had to enter through the “back door,” but this didn’t always prevent street harassment and violence. At age 25, he bought the Hotel Washington in 1975. Within a few months, he opened the Barber’s Closet—and it was just the beginning of the renaissance. He transformed the greasy spoon “Hot L Cafe” into Café Palms. Club De Wash opened in 1977, Rod’s in 1979, NewBar in 1984 and MicroBar in 1995.

Rodney Scheel was one of Wisconsin’s best-known gay rights and AIDS activists. He founded the MAGIC Picnic, an annual celebration of gay Madison, a tradition that continued until 1998. The Picnic began as an employee appreciation event, but at its peak, it was one of Madison’s largest annual fundraisers. Hundreds of thousands of dollars were raised over the years for critical LGBTQ causes. (The MAGIC Picnic was resurrected as the OutReach MAGIC Festival in 2019.)

Rod’s became one of the most popular—if not most notorious—gay bars in the state. “If you came into Rod’s with underwear on, you would probably have them torn off and they would get tied up on the pipes,” said Greg Scheel.

Meanwhile, high school and college students from across the state would travel to NewBar for Tuesday’s 18+ nights, when the lower level was reserved for minors and the upper level for adults.

By 1990, AIDS and HIV infection was reaching critical mass in Wisconsin. Over 80 funerals were held for Hotel Washington regulars during this dark era. The Scheels allowed people suffering from AIDS to move into hotel rooms if they were unable to maintain their independence. This inspired Rodney Scheel’s dying wish: To open a home where people with AIDS would be treated respectfully and competently.

Sadly, Rodney Scheel died in July 1990 at the age of 39.

The Hotel Washington was open 365 days a year and offered holiday events so nobody was left behind. It was a huge supporter of local pride organizations, and it was lovingly reconstructed on many a pride parade float over the years.

Steve Starkey, then executive director of Outreach LGBT Community Center, said “There was something for everyone. If you wanted to go dancing, you could do that. If you wanted to go to a leather bar, you could do that. If you wanted to hear music, you could do that. If you wanted to go out and eat, there was Café Palms. It was one-stop shopping.”

“If you were gay and didn’t want anybody to know you were gay, you went into one of the straight clubs, and then you would sneak into the back staircase and go to one of the gay clubs,” said Greg Scheel.

Here are some of those stories.

Memories of the Hotel Washington: Michael

“Hotel Washington played an important role in my life,” said Michael, a 30-year Madison native. “I saw Sarah McLachlan at Club De Wash. My husband and I had our first date at Café Palms. But it’s NewBar that had the first, and probably most lasting impact on me.”

“I came to UW-Madison in 1990 from a small town in rural Wisconsin,” said Michael. “and it was definitely overwhelming. Coming from where I’d been, it was a whole lot at once. So, one night, I went with a group of friends to the Hotel Washington, got separated from most of them, and got lost”

“Somehow, we came upon it, and it was spectacular. It was a great, gigantic old building, and it had such an imposing presence to it. I don’t even recall if we got into NewBar the first time, but I was just so struck by the architecture and the experience of the building itself for days afterwards. Nothing else in Madison matched it, then or now.”

“I’d read about New York nightclubs in high school and expected something like that, but that wasn’t NewBar. It was modern and worldly but still very small-town. I always thought Café Palms and Barber’s Closet were so glamorous. The Hotel Washington was a really great place to have in my life at that time. I lived in the Wiedenbeck Building (619 W. Mifflin St.) for a summer, so I could spend a lot more time there.”

“We went to Café Palms two weeks before it burned down, after not being there for years, not even realizing it would be our last visit,” said Michael. “We drove right past the fire as it was happening. I remember thinking, this is just crazy, what is Madison going to be like without it? And then I remember this feeling of nothing happening—and then, nothing ever happening again. Nothing ever rose up to replace it. But how could it? The Hotel Washington was unique to the point of being irreplaceable.”

Memories of the Hotel Washington: Emily

Emily came to Madison in fall 1990 and stayed for 15 years. After graduation, she settled down, got married, had kids and left the downtown scene. Still, her memories of the Hotel Washington stay with her today.

“I still remember the first time we went,” said Emily, “thinking how it was a little bit of a lot of things. It had this cool vibe, but kind of a city vibe, the air of something slightly dangerous that appeals to you at that age. That air was exhilarating to me.”

“I remember staying at Café Palms late at night, after the bars closed, and being so poor, and so young, we’d all share a gigantic plate of French fries. I remember sitting around and smoking and acting so intellectual at age 18.”

“One night, I was invited upstairs into the living quarters for some reason. It was this totally different world from where I came from. There were people in various states of undress, with their room doors open, and it all felt very debaucherous, like some kind of cabaret.”

“I remember Rod’s—and I’m not sure how I got in—and seeing men with Freddie Mercury mustaches and harnesses for the first time. I walked into that back room with all the TVs showing porn, and absolutely nobody was watching it! Nobody was paying attention at all. I’d never seen a lot of porn, much less this much porn. And here, everyone was standing around, sipping their drinks, acting blasé.”

“I just remember thinking that outsiders looked at our group and wanted to be part of it. We were really something. I can’t believe how many hangers-on we attracted. I remember people taking videos of us because we were unlike everyone else in the bar.”

“NewBar was the first place I ever saw a drag queen. I was so young, and so sheltered. They were unlike anything I’d ever seen before. Just so fabulous and glamorous. One of my favorite memories was voguing with a male model on the dance floor at NewBar. It was really fun, and I thought I was so cool. I hope nobody has videos of that!

“It was such a part of our lives for so long. First, in the dorms; then, when I lived half a block away. There weren’t really many places to go. Madison seemed so small and so limited.”

“Nothing else stands out as a place where the gay community can come together in the way they came together at the Hotel Washington. I felt like we lost our rallying point.”

Memories of the Hotel Washington: Dave

Dave came to UW-Madison in 1989 and stayed for five years.

“I have fleeting memories and thousands of photos from that era,” said Dave. “Madison felt so big-city to me. I was on my own, with no supervision at all, and suddenly had that self-aware moment where I realized I could do anything I wanted. I can dye my hair any color and nobody will laugh. I can date whoever I want and nobody will judge me. I’d never been in such a bubble before, and it was liberating.”

“Eventually, I realized I had access to bigger cities, like Milwaukee and Chicago, where I could get a better understanding of gay life.

“I remember my first exposure to Hotel Washington. We went to NewBar, at the height of Madonna’s “Vogue” and the Truth or Dare Tour. The Ten Percent Society dances had been a place to dance, and I loved dancing in that giant hall. But NewBar was the scene we saw in Andy Warhol’s Interview: This was our Studio 54, this was our Club MTV. And then, the hierarchies got built: who’s in what clique and who’s built what name for themselves. I really felt like King of the Twinks. I surrounded myself with people who were glamorous, eccentric, monied, and fun. I wasn’t super close to them, but they made me look good. It was all so much fun.”

“I started to date older men, which changed everything,” said Dave. “I discovered the Barber’s Closet, where I learned about high-end liquors like gin and whiskey. From there, I fell into Café Palms where I could find an alternative culture not found at the Rathskeller. I wanted to talk about John Waters or Fran Liebowitz, not Nietzsche, and you could do that there.”

“Then came Rod’s! Oddly enough, my first experience was with a group of lesbians in the summer of 1991. I remember seeing those massive tube televisions hanging from chains on the walls. They had to be at least 75 pounds each. I was excited to find such a salacious place. Was this real life? Was this actually happening? I jumped right into it.”

“I got into the grunge scene in 1993. My friend circle was changing rapidly, as people were breaking up, choosing grad schools, even leaving Madison. Club De Wash drew me into the live music scene. I was amazed by the amount of access Madison had to emerging talent. It was very straight, but it was my last stop in my Hotel Washington journey.

“NewBar was a moment that held my interest for about two yeasr, before I went downstairs to Palms, and then Rod’s, and later branched out to the Cardinal, Genna’s, and other places. I grew up in the Hotel Washington, or shall I say, I grew as I worked my way down from the third floor to the street. I realized I didn’t have to be gay 24/7. I had other options.”

“I was shocked when the hotel burned down,” said Dave. “I was living in Ann Arbor at the time and hadn’t thought about it for two years. And then, I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I went through a grieving process of sorts. I called my old friends from Madison and we rehashed all the old stories, just for old times’ sake. Therapeutically, it was nice to revisit the old days because everyone remembered them differently, as if we had all seen different versions of the same movie.”

“The Hotel Washington resonated for me at a time when I needed it. Like the formative years of high school, it felt like an initiation, something I needed to endure as a young gay man, to get it all out of my system. I wasn’t thinking about my mortality. I thought I was invincible.”

“I’ve been telling my stories as a cautionary tale to young men currently living my past life. They don’t always want to hear it, but I won’t stop sharing it.”

The long goodbye

At one point, some believed that Rod’s could be salvaged, and could reopen within a few months, with the rest of the building eventually reconstructed over it. The Scheels hoped to add a fourth story to the hotel, double the number of hotel rooms, and expand into the neighboring gas station space. The Hotel Washington team set up a temporary office at the train depot and pursued their ambitious restoration. They even ran a full page ad in the Madison Gay Directory saying the Hotel would reopen in fall 1996.

But, only six months after the fire, it became clear that reconstruction wasn’t going to be quite so easy.

Contractor estimates had soared far beyond available financing. At the same time, scaling back the plans reduced the revenue generating capabilities of the hotel, which in turn reduced the amount of financing offered. Because of the hotel’s age, it was grandfathered from some building and zoning codes that would have applied to a new building. And the insurance policy only covered the Hotel Washington’s market value, not the cost of rebuilding it. In effect, the cost of rebuilding would be twice as much as it cost to buy an existing building. The project was over $400,000 short on funding.

“It’s really devastating not only to myself, but for everyone else,” said Greg Scheel in September 1996. “We have orders from the city to fill in the hole. City regulations only give you so much time to either rebuild or cover up the hole. Ours must be covered by the end of October.”

The struggle to rebuild the crown jewel of Wisconsin’s LGBTQ social spots was over. The Scheel family began considering other locations for the Hotel’s businesses.

Steve Starkey, former co-chair of GALVANIZE and Director of Wisconsin Community Fund, said, “Madison isn’t a real big town. It’s not like Milwaukee where there’s lots of different bars and lots of possibilities. It was a community center, because there were five different bars in that building. There won’t be anything on the scale of the Hotel Washington for some time. People have been awaiting the rebuilding. It’s going to be hard to accept it will never come.”

“How do you say goodbye to an old friend, especially when it’s a wonderful building that had been the hub of gay life in your city?” asked The Wisconsin Light. “The Scheels deserved better. They waged a tenacious battle with a willingness to risk everything for the community they have for so long supported. They simply ran out of time. They deserved to win this battle. Part of our disappointment is knowing how they must feel. Our hearts are broken along with theirs.”

A wound that never heals

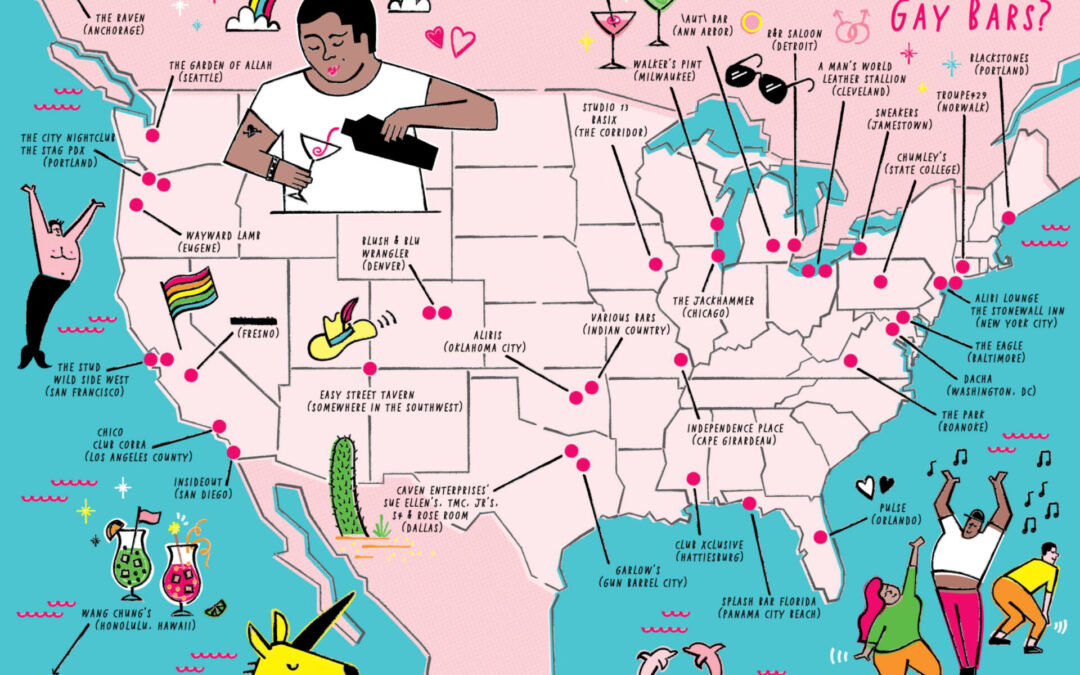

Without the Hotel Washington, one-stop shopping was no longer an option. Madison’s gay bars were no longer together in one geographic area, like in other major cities, nor did Madison’s gay community seem to have a spiritual center. New gay bars, like Club Five, were outside the downtown area and only accessible by car. Many found the newer bars cliquey, unfriendly, or exclusionary, serving only a niche of the overall community. Meanwhile, many Hotel Washington regulars began leaving Madison.

Within just a few years, Madison felt like an entirely new city—and a decade later, even the concept of a Hotel Washington seemed unthinkable.

Four years later, Chris Ott asked, “Why is Madison so Gay Unfriendly?” in June 2000’s In Step:

“Hotel Washington burned down and nothing has ever replaced it. I’ve talked with a bunch of Madison residents about the lack of “gay space’ in town. What I heard from everyone is how different things were when the Hotel Washington was still around. It was a place to talk, dance, have a drink, eat or just hang out, all in a gay-friendly environment.

“But here’s the problem: as good as the Hotel Washington was—Madison doesn’t have anything like it anymore, even spread throughout the whole area, not to mention in one space. I don’t mean to put down the gay space that Madison does have. Still, something’s missing.

“Especially for the growing number of us who came to Madison after the demise of the Hotel Washington, the city feels more like a town of 20,000, not 200,000.”

“The Hotel Washington just seems to be one of those stories we hear about the 60s, 70s or 80s,” said Amber Halverson, bar manager of Plan B, in 2015. “It seemed like a crazy time when anyone could be a rockstar.”

Toni Ziemer hosted a reunion event, “20 Years after the Fire: A Shindig” at Genna’s in 2016. While researching the hotel, she learned that the 1996 fire fell—almost to the date—on the anniversary of the property being renamed Hotel Washington. Ziemer has been planning a book of her own.

Some spectators still own bricks they took from the scene of the fire. Today, they’re the only physical remains of this building that meant so much to so many.

In 1999, the Hotel Washington lot was replaced by a gas station and convenience store, which in turn, was replaced in 2020 by West Washington Place, a five-story 51-apartment complex offering “luxury penthouse lofts.” Madison politicians saw the redevelopment as a good thing: An investment in downtown that would attract more urban dwellers. Critics saw the building as more of the same dull and soulless architecture 21st century Madison was flooded with. While Hotel Washington alumni hoped for some connection—any connection—to their historic landmark, there doesn’t seem to be any at all. Not even the address is the same.

“It’s dreamlike to think it’s been gone 25 years now, like none of our experiences ever actually happened,” said Dave. “There’s no proof to point at. But this entropy is all part of the human experience. We get used to it, we accept it, we move on, but we just keep telling the same stories about a place that no longer exists.”

I LOVED going to Hotel Washington. I was there with my partner the night before the fire. I lived in an apare Capitol Square and heard the fire trucks. My partner and I found out that The Hotel Washington was on fire. We walked to the Hotel Washington and joined the crowd that had started to gather. It was a very emotional time. This article has brought back so many memories.