In May of this year, the first case of monkeypox was confirmed in the United States, in Boston. The virus, which had previously been endemic to parts of Central and West Africa, had already worked its way across Europe starting early in 2022, when outbreaks hit the UK, Spain, and other countries where it had never been seen before.

While that raised alarms for those on the front lines—largely within the LGBTQ community—the rest of the world was slow to react. Since then, the virus has spread to at least 50 countries, with more than 42,000 confirmed cases, mostly in Europe and the United States.

It is not a strictly sexually transmitted infection (STI), but since monkeypox is spread through close, sustained, personal contact like sex, kissing, and kink play, sex plays a large role in its spread.

The largest pool of those infected have and continue to be queer people and their networks. The virus isn’t limited to impacting LGBTQ people, of course. That hasn’t stopped some of the old familiar stigmas and blame-games from rearing their heads. Misinformation began spreading almost as quickly as the virus itself. Coupled with a slow and often piecemeal initial response by governments and health organizations, that’s resulted in yet another public health crisis where queer folks suffer disproportionately.

“We’ve seen so many attacks on Pride and drag story times, it feels like we’re in a very precarious situation with this disease outbreak in particular,” says AJ Hardie, Program Director at OutReach LGBTQ+ Community Center in Madison. “But I think a lot of the lessons that come out of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, for instance, are about how we as a community have to have each other’s backs, and inform ourselves. It’s an unfortunate reality that, for a lot of queer people and especially a lot of trans people, there’s already a lot of advocacy that we have to do in healthcare settings. This is just another thing that we’re going to have to self-advocate for testing and vaccination.”

Those lessons have been hard-won by the LGBTQ community and can benefit us—and the world—in this current crisis. Where mainstream health and government entities may not be consistently reaching the most impacted communities, Hardie and Outreach are using their platform to provide accurate and up-to-date information directly to LGBTQ people. Diverse & Resilient in Milwaukee has been hosting vaccine clinics. Individuals have been helping friends and loved ones get accurate information and seek out care.

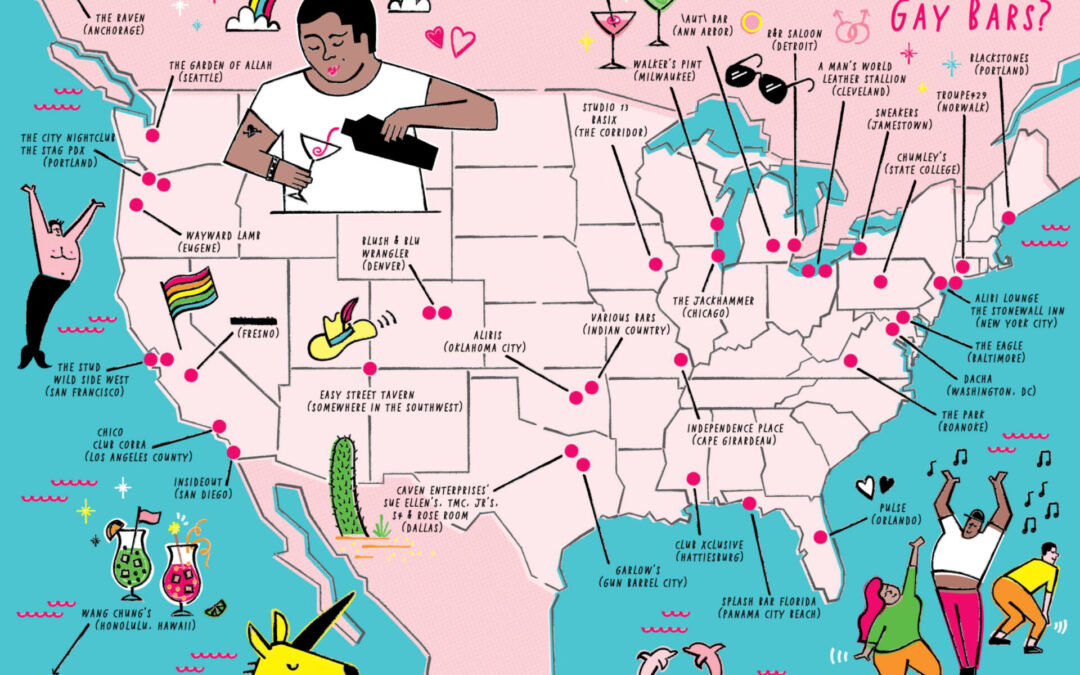

Nationally, queer activists and experts have gotten to work advocating for better testing and vaccine distribution, especially in New York City, the epicenter of the outbreak in the U.S. And methods of risk reduction, similar to efforts around HIV/AIDS and Covid, are being developed and disseminated via queer networks.

“It’s safer sex practices that we should be doing anyway, because we’re worried about STIs, we’re worried about HIV, all these things, and that really comes into play with monkeypox,” adds Hardie.

Given that Wisconsin tends to see a lag time in infections compared to places with larger populations, too, it can provide an opening to prevent outbreaks from spreading exponentially, explains Dr. Ajay Sethi, professor of Population Health Sciences at UW-Madison.

“That lag time gives us a little room to educate people so that they can take the necessary precautions,” says Sethi, “and then we can monitor the situation to prevent a worse wave.” He cautions against only caring about the situation in Wisconsin; however, given that the problem is global. “[Monkeypox] can be reintroduced in Wisconsin later if it’s not contained in other places that are adjacent. We have to care about the whole.”

Sethi also emphasizes the importance of clear, honest discussions around sexuality and disease transmission, both in the LGBTQ community and at large. He notes that too many reporters and media figures tend to shy away from frank talk about sex, and that, like with HIV/AIDS, that only leads to worse outcomes.

“We need to do a better job of talking about sex in general, and then recognizing that people of any identity will have sex and that’s healthy and normal and good,” Sethi explains.

When it comes to monkeypox, the line shouldn’t be that people need to stop having sex, but that there are things we can do to reduce risk. Right now, most of that education is happening person-to-person, but it needs to be shared more widely.

“What I see is a community of people who have been left without access to the care that they need, advocating for themselves and for others and going to extraordinary lengths to try to minimize viral risks,” Joseph Osmundson, a queer health advocate and clinical assistant professor of biology at New York University, recently told Vox. “All the while, their suffering is not being taken seriously.”

“Gay sex is a fact of life. Gay sex exists on planet Earth, you will never change that, whether you want to or not. Gay sex will always exist, gay sex doesn’t drive anything. It’s like the sun in the sky or the tide going in and out,” Osmundson went on to say. “So when epidemics spread through gay sexual networks, we want to be very precise about that language. And also to be clear that sex is a normal and healthy behavior. And our goal in biomedicine should be giving people all the tools that they need to make the best decisions and, in this case, have sex with the lowest risk possible. In this case, the drivers of the epidemic are the structures globally that have led to vaccines, tests, and treatment all existing for a virus and yet being almost entirely inaccessible. We cannot change the fact that gay sex exists, but we can change the fact that the Jynneos vaccine is not globally available. We can change the fact that TPOXX is largely inaccessible.”

Some of that advocacy and hard work is beginning to pay off. The White House in late August announced that it was ramping up distribution of vaccines and antiviral treatments, with special focus given to large LGBTQ gatherings and events. This came after the administration officially declared monkeypox a public health emergency, freeing up resources to help battle the virus.

Whether it will be enough to prevent a larger outbreak, or be too little too late, remains to be seen. In the meantime, the best medicine is good information and getting vaccinated as soon as you’re able/eligible.

About the vaccine(s)

As Osmundson notes, there are two vaccines already in existence (developed for smallpox, which is genetically similar) that can be used to help prevent monkeypox infection.

The Jynneos vaccine is the preferred method and what’s currently being distributed and used in the United States. It’s approved for use in adults 18 and up who are considered high risk for infection and has been in use in Europe since 2013 and the U.S. since 2019. The vaccine usually requires two shots given 28 days apart, with peak immunity being reached 14 days after the second dose.

The older ACAM2000 is a single-dose vaccine, and takes four weeks after vaccination for its immune protection to reach its maximum. However, it has the potential for more side effects and adverse events than Jynneos. It is not recommended for people with severely weakened immune systems and several other conditions.

Ryan Westergaard, chief medical officer with the state Department of Health Services, told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that, as of mid-August, Wisconsin had received about 3,286 doses of the 5,986 it has requested from the federal government. Due to an inadequate supply of vaccine nationally, states are only allowed to request additional amounts once they’ve distributed at least 90% of their supply.

Given the continued supply chain issues, priority is still being given to people considered to be at high risk for contracting monkeypox. According to the Wisconsin DHS, that includes:

- People who know that a sexual partner in the past 14 days was diagnosed with monkeypox.

- People who attended an event or venue where there was known monkeypox exposure.

- Gay men, bisexual men, trans men and women, any men who have sex with men, and gender non-conforming/non-binary individuals, who have had multiple sexual partners in the last 14 days.

DHS maintains a list of locations across the state with publicly available vaccine appointments at dhs.wisconsin.gov/monkeypox/vaccine.htm. As with any public health emergency, it’s important to check back for updates often, as the situation changes and more vaccine doses are made available.

There is also an anti-viral treatment: TPOXX (tecovirimat). It can help patients avoid the most severe forms of the illness. Thanks to bureaucratic hurdles, it’s been nearly inaccessible. The Biden-Harris Administration recently announced, however, that it would relax some of those rules and release 50,000 courses of the treatment to different jurisdictions at the end of August.

What monkeypox is—and isn’t

What is monkeypox and how serious is the current outbreak? Monkeypox is a rare but potentially serious disease that is caused by the monkeypox virus. The virus is from the same family of viruses as smallpox.

People with monkeypox get a rash that may be located on or near the genitals (penis, testicles, labia, and vagina) or anus (butthole) and could be on other areas like the hands, feet, chest, face, or mouth.

- The rash will go through several stages, including scabs, before healing.

- The rash can initially look like pimples or blisters and may be extremely painful or itchy.

Other symptoms of monkeypox can include:

- Fever

- Chills

- Swollen lymph nodes

- Exhaustion

- Muscle aches and backache

- Headache

- Respiratory symptoms (e.g. sore throat, nasal congestion, or cough)

You may experience all or only a few symptoms.

- Sometimes, people have flu-like symptoms before the rash.

- Some people get a rash first, followed by other symptoms.

- Others only experience a rash.

Monkeypox symptoms usually start within three weeks of exposure to the virus. If someone has flu-like symptoms, they will usually develop a rash 1–4 days later.

Monkeypox can be spread from the time symptoms start until the rash has healed, all scabs have fallen off, and a fresh layer of skin has formed. The illness typically lasts 2–4 weeks and is rarely fatal.

Monkeypox can spread to anyone through close, personal, often skin-to-skin contact, including:

- Direct and sustained contact with monkeypox rash, scabs, or body fluids from a person with monkeypox.

- Touching objects, fabrics (clothing, bedding, or towels), and surfaces that have been used by someone with monkeypox.

- Contact with respiratory secretions.

This direct contact can happen during intimate contact, including:

- Oral, anal, and vaginal sex or touching the genitals of a person with monkeypox.

- Hugging, massage, and kissing.

- Prolonged face-to-face contact.

- Touching fabrics and objects during sex that were used by a person with monkeypox and that have not been disinfected, such as bedding, towels, fetish gear, and sex toys.

A person with monkeypox can spread it to others from the time symptoms start until the rash has fully healed and a fresh layer of skin has formed.

There are certain things about how the virus is spread that are still unknown and being researched. For instance, we do not yet know if the virus can be spread when someone has no symptoms, how often monkeypox is spread through respiratory secretions, or when a person with monkeypox symptoms might be more likely to spread the virus through respiratory secretions, or whether monkeypox can be spread through semen, vaginal fluids, urine, or feces.

0 Comments