As we walk into the stories of Dr. Katrina Daly Thompson (they/them) and another queer Muslim leader, QQ (she/her), who wishes to remain anonymous, we begin by bringing forward two gifts they offered from faith to queer, and from queer to faith. Katrina offers this teaching from Islam: “Everywhere you look, there is the face of God,” while QQ offers another teaching: “If you can’t change something with your voice, try to change it with your hands. If you can’t change something with your hands, try to change it within your heart.” Both people queerly walk in their own understandings of their faith and queerness.

For QQ, family is core. She was raised and remains in a loving Muslim family. And while she needs a degree of anonymity, she feels that they accept her queerness “without us talking about it in a way where it’s like ‘we love you no matter what.’” QQ speaks of comfort among younger people in her family and that “among older people there are hints of them wanting to know more, wanting to be educated.” QQ spoke about how her “mom watched a documentary about a trans youth in Egypt, and she was talking to me about it, about how, no matter what, a human is a human, and it’s none of our business how someone feels or how someone wants to live their life, and that that is the whole basis of our religion.”

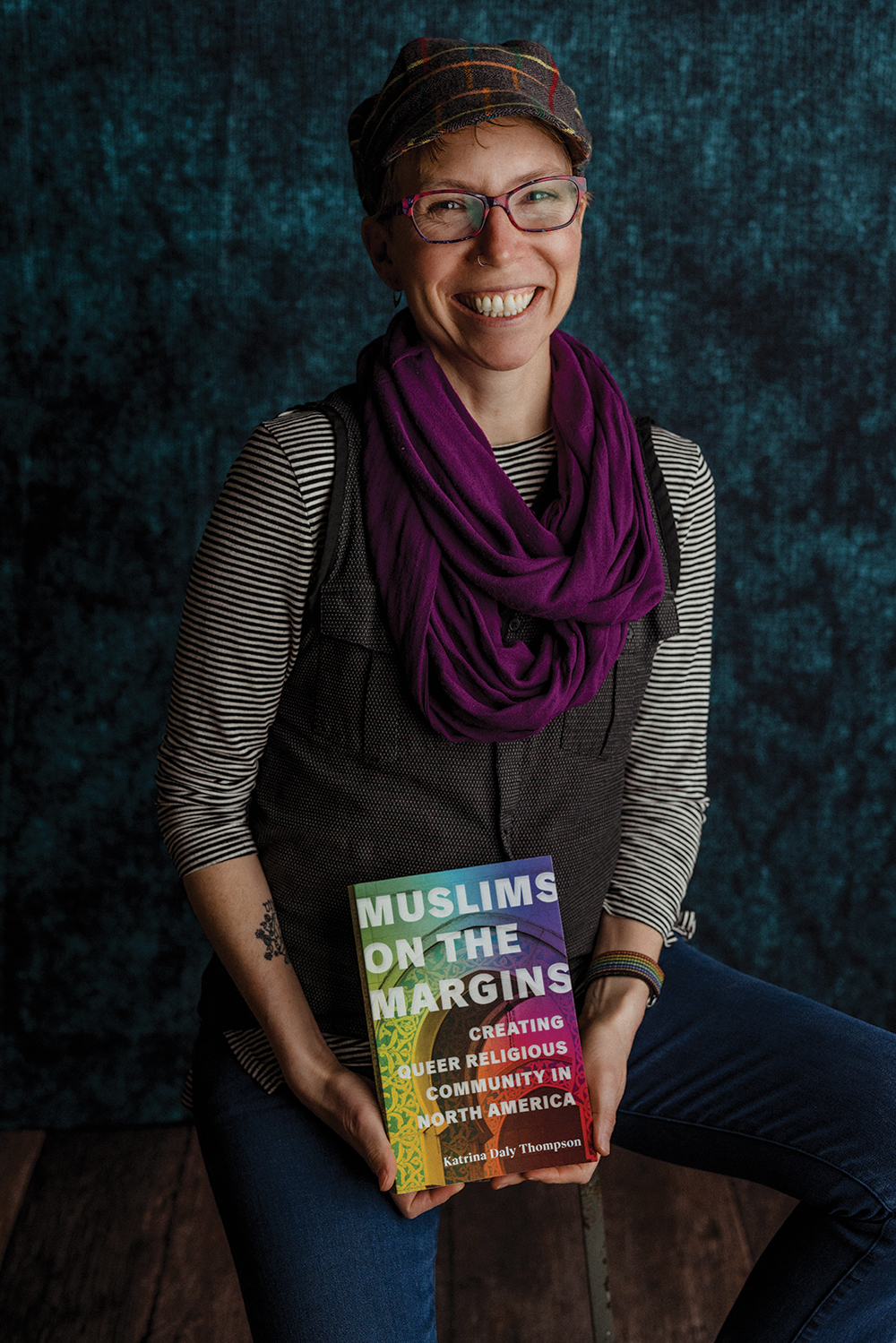

Katrina, Evjue Bascom Professor in the Humanities at UW-Madison, and also an author, whose most recent title is Muslims on the Margins: Creating Queer Religious Community in North America is a later convert to Islam, with a background in loving Atheism with a strong interest in Buddhism. Katrina’s childhood might seem like it could not be more different from QQ’s. Their family was non-religious, but as a youth they joined a friend in a Christian youth group. For them, that group was “mostly social,” but even so, they were “drawn to some of the spiritual aspects in a way that I only realized later in life.”

As they grew up, Katrina drifted away from the Christian community they had been part of and “didn’t see myself as religious at all.” They did “develop a kind of academic interest in Buddhism,” but it wasn’t until they were done with graduate school and in their first job that they began to seek out faith again. They had “heard some vague things about Unitarian Universalism (UU) churches that I thought might fit with my feminism and be welcoming of me as a queer person.” They joined a UU church “and that became a really important community for me.”

They continued to develop their understanding in faith while in Tanzania doing research. Katrina says, “I spent the summer of 2009 there doing research, and while I was there I ended up getting involved with a Muslim who asked me to convert to Islam.” Their initial reaction? “I balked at this. I imagined that becoming Muslim meant having to give up my ideals as a feminist and hiding my queerness. But I was committed to that relationship, so I agreed to explore Islam.” Leaning into their academic training and heart, Katrina “just started reading as much as I could about Islam and Googling things like ‘Islam and feminism,’ ‘Islam and queer,’ and so on. I discovered, to my surprise, that there was quite a bit of scholarship among American Muslims who were arguing that Islam does not forbid homosexuality.” And in their research, Katrina also discovered that there are groups of queer Muslims and Muslim feminists. Later they would participate in and develop queer faith communities. They spoke with their then-partner and “shared what I was learning and said ‘if I converted, this would be my approach to Islam, are you comfortable with that?’” Katrina still struggled with this decision because, “With my atheism, how could I be a Muslim if I didn’t believe in God?” The answer to that question came with the young adult UU group they were part of. The group regularly went out to visit different worship spaces, and on one visit to a megachurch, “one of the songs that we sang mentioned God. I remember initially feeling a little bit uncomfortable, but the rest of the words were really beautiful, and so I just did this mental translation of substituting Love or The Universe or different terms that are more real to me for God. And then the song made perfect sense, and was really beautiful and touching. So I realized after that, that it wasn’t that I didn’t believe in God; it was that I didn’t believe in this notion of an anthropomorphized white guy in the sky.” For Katrina, this realization meant that they “could believe in God. I could be a Muslim even if my conception of God might be different” from that of the Muslims they knew in Tanzania.

QQ came into her queer identity at 22, when she “suddenly felt these emotions” that were “so natural, so fulfilling and just pure.” The experience was “really special in that my Muslim faith wasn’t questioned by my sudden realization of my true identity, in fact it was strengthened because I couldn’t imagine that something so straightforward, something so powerful, could be a sin.” Can you feel the gift she gives to faith in this pure love? QQ names the gift religion gave her beside the gift that queer gives to faith, as queered understanding helps lift faith from human limits, naming that she is “an incredibly lucky person to be Muslim and to be queer in this time period because there are so many resources that have guided me and helped root out that internalized homophobia that I might have felt because of my religion.” As she came into her own queerness, QQ sought an understanding of why Islam seemed to be against all the beauty that she felt in her queer relationship, noting, “I think my first step was really dissecting culture away from religion, trying to figure out what was something that was sourced out of humanity and those directions that were straight from God.” In taking this approach, going directly to the source, she “found a lot of reassurance that my feelings were validated and were real.” As she read more she found that in “the Qur’an I was able to justify my existence as a human being, as someone who was worthy of being all of who I am.”

In her study, QQ came to understand that “the bigger picture is that God is very forgiving. God is more understanding than we are, and isn’t a vengeful deity. The scripture and the traditions of the prophet reassure me that being queer is worthy.”

As QQ reflected on the question of the gifts she brings to faith, rooted in family and queerness, she said, “I think it’s made me love God more.” She roots her love of God in community with “my trans friends or my gay friends or asexual friends,” and in her own growing understanding of her queerness. She felt “such awe of how magnificent it is to be part of such a diverse and beautiful human species where we have such a capacity for love that it transcends even our own minds and our own understandings. He created all of this, and he created me, and he created my queerness.”

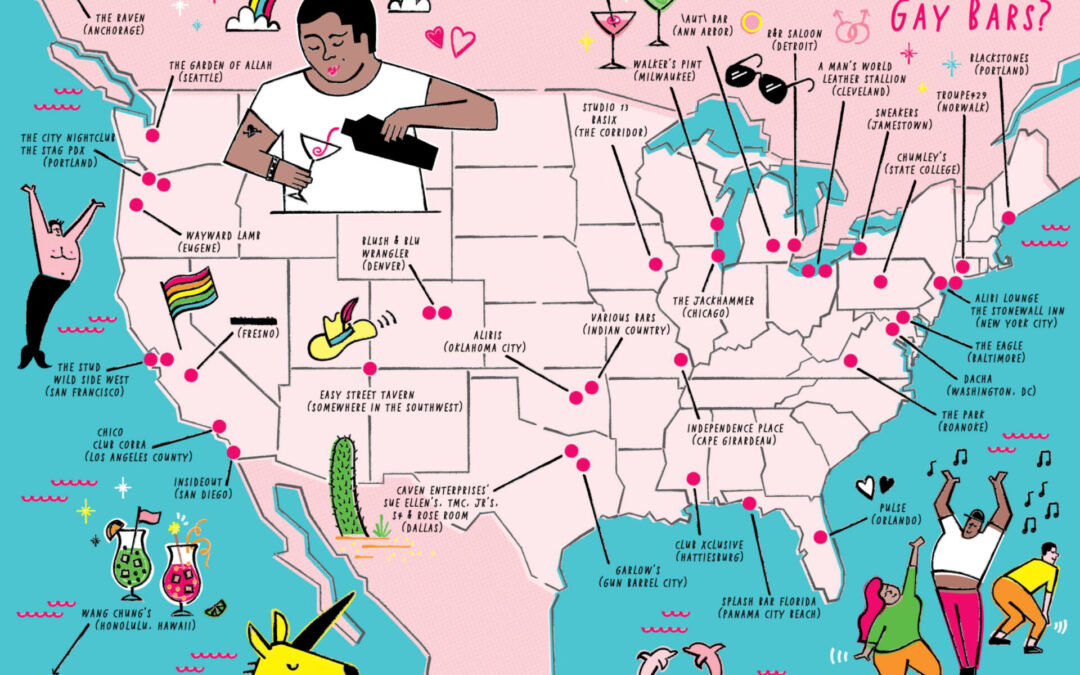

Katrina took me into some of the work that they did in developing their book on queer-inclusive Muslim groups. They shared many stories but one that stood out reinforced the gifts that queer brings to faith. Katrina names that there are arguments in Muslim communities that criticize progressive and queer understandings as just people who chose to “bend their interpretation of their religion to match the things they already believe” like the idea that “homosexuality is allowed” or that “it’s okay for men and women to pray together.” But Katrina rebuts these arguments, saying, “My research shows that a lot of people who come into these communities don’t initially believe those things.” People Katrina interviewed said things like, “The first time I prayed next to someone whose gender was different than mine, I felt weird, you know? It’s not something that I was comfortable with but over time, doing it made me feel comfortable and made me realize that there’s nothing wrong with it. It’s not a sin.” And in this work, Katrina names this gift of “people who talked about that embodied experience of being near someone who is different from them helping them to change their beliefs. It’s experience leading to belief rather than belief leading to different practices.”

Katrina names the gift queer and inclusive spaces bring to faith, saying “the most common word in the Qur’an is ‘compassion.’ Every single verse starts with, ‘In the name of God, the most compassionate, the most caring.’ And so Muslims who take a more inclusive approach to Muslim community really focus on that and remind us that God is a compassionate figure, that the Universe is compassionate and therefore we should all be compassionate to one another.” Compassion is our calling, and we are each to work, according to our own abilities, toward love.

Vica-Etta Steel is a Vicar at St. John’s Lutheran where she preaches and does outreach. She also serves as a public chaplain at the Madison Farmers’ Market, at coffee shops, and on Tik-Tok. It is her joy to work with people across the spiritual spectrum who have returned to their queer family, Jewish, Pagan, Christian, to name a few, and the many atheist and agnostic people who taught her how to believe deeply in love, in community.

0 Comments