“My mother did not play mahjongg, and my father did not drive a Cadillac.”

It’s been a while, but I’m pretty sure that is how I started one of my essays when applying for graduate school. The task was to explain in some measure who I was, where I came from, and why I wanted to do graduate studies in public policy and journalism.

Looks like I decided to declare my outsider status early on.

I grew up in Bellmore, Long Island. Remember Joey Buttafuoco and Amy Fisher? Fisher, dubbed the “Long Island Lolita” for shooting Buttafuoco’s wife while having an affair with Joey, went to my high school—though more than a decade after I graduated. More distinguished alumni include economist and New York Times columnist Paul Krugman and fashion designer Michael Kors.

Bellmore was a suburb of New York City, a 50-minute ride on the Long Island Railroad or a car ride of several hours, depending on traffic. I lived in a newer part of town, along a canal that emptied into the Great South Bay.

Many of the families had left New York’s boroughs for promised good schools, clean living, and the relatively safe life of the suburbs. There were enough Jewish families that the school district closed for the High Holy Days in the fall; these newer arrivals, which also included Italian and Greek families, were often first- or second-generation immigrants. For reasons still unclear to me, someone thought it would be a good idea to change the nuns to social workers when we performed The Sound of Music in elementary school! “How do you solve a problem like Maria,” sung by three social workers (including yours truly) makes a certain sense when you think about it.

Bellmore was a community of strivers—education was a priority, extracurricular activities were encouraged, and almost all students were on a college, if not professional, path. Money was an object of desire and a measure of success; displays of wealth, whether in the form of jewelry, clothes, or cars, were common.

My parents were of a different ilk. My father, a dentist, and my mother, a reference librarian, believed strongly in education but did not see it as solely about grades or a means to an end. Accumulating knowledge and being intellectually curious was something worthwhile and noble in itself—and personally enriching to boot. I remember once studying late for a science test until my father suggested that I call it a night, saying I had studied enough and would do fine. They were comforting words, given the competitive pressures at school.

My dad was an old-school dentist. One chair, one assistant. He worked early and late, Monday through Saturday, to accommodate his patients’ work schedules. You didn’t have the money to pay? The matter was left there. He was a great dentist (and, I heard, a pretty good therapist), but not a great businessman. My mom went back to graduate school and became a beloved, though slightly feared, reference librarian. You will not crack your gum while others in this room are trying to concentrate! I heard from more than a few patrons who credited her with helping them through graduate school. When she retired from Bellmore Memorial Library, they named the reference desk after her.

Neither of my parents brought in big bucks. Hence, no Cadillac. My parents also never seemed to fit in socially, though I’m not sure my mom would have played mahjongg even if asked—playing games was not her thing.

The sum total is that I don’t think they ever felt part of the community that they had moved to with such high hopes. They felt like outsiders, and, to some extent, so did I.

Supported, Not Directed

My mother was perhaps most ill at ease. She grew up in Kansas City, Missouri, and was a Midwesterner at heart (you say creek; I say crick). She lived through the Great Depression and legal segregation and shared stories of that time.

She told me about how Hallmark Cards, based in Kansas City, did not hire Jews when she was growing up, and how she and a black friend were denied service at a luncheon counter. I remember her grief at the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. I also learned that her parents, immigrants from Lithuania, had been active in helping relatives escape from Nazi-occupied Europe. When going through some papers collected by my parents, who are both dead, I found letters my maternal grandfather wrote to diplomatic offices vouching that these relatives would have a place to stay and work if they were allowed to immigrate to the United States.

My father grew up in the Bronx, surrounded by relatives in neighboring apartment buildings. He was quiet and did not talk much about himself. He went into the army immediately after dental school, seeing combat during World War II as part of the Third Armored Tank Division. He brought back a missile that someone, somehow, had converted to a shot glass dispensary. Scotch was his drink.

Both of my parents were readers and they kept up on current events. We had two papers delivered daily to our house, The New York Times and Newsday, and my mother always had the news playing on the radio in the morning. She taught me how to read before I started school and, later, how to organize a paper and argue a point. I guess she was my first editor. She was passionate about the written word and passed that passion on to me.

My parents also instilled in my brother and me values of social justice, fairness, and kindness. They were helicopter parents only when it came to matters of safety. I always had to have money for a phone call (yes, this was before cell phones) and I remember a lot of embarrassing calls at friends’ homes about my whereabouts.

But they were remarkably hands-off in other ways. They never forced me into a sport or hobby or tried to steer me on any particular path. I felt supported but not necessarily directed.

For a long time, I did not know what I wanted to be. My very circuitous route to journalism should give those without a clear career focus hope that they, too, will someday find their way.

A winding road to writing

College, unfortunately, did not clear much up for me. I attended a liberal arts state college, SUNY-Binghamton, but it was in many ways a repeat of high school—good academics but insular. The student body, at least in 1978, was pretty homogeneous; I think about 30 classmates from high school joined me there.

Through my history major I was turned on to social history, which focuses on the lives of ordinary people, rather than those of kings and presidents. It provided a good perspective for future reporting. Two semesters of art history also opened up a new world to me; my friend Marie and I sought out many of the masterpieces we studied in those classes on a trip to Europe after college.

I took one course in journalism and volunteered briefly at one of the campus papers but it was not love at first write. More significant was a work-study job in the Women’s Studies program; already a feminist, I became more interested in women’s issues, including poverty and reproductive healthcare and access. I thought about going to graduate school for history but made no real moves in that direction.

After graduating college in 1982 I moved back home with my parents and purchased a skirt suit and pair of heels, the job-search uniform of the day. I’d ride the Long Island Railroad to Manhattan to meet with hiring agencies. I was asked at one interview to list some things I like to do; “research and analysis,” I answered. I remember thinking to myself how vague that sounded.

I got an entry-level job as an editorial assistant at Computers and Electronics, which had recently morphed from Popular Electronics. It’s the first time I witnessed how the march of technology would change people’s jobs and livelihoods. Another takeaway? No need to leave two spaces after a period. Also, refusing to fetch a cup of coffee for the editor-in-chief raises questions about whether you’re a team player.

A year later I went to work as the editorial assistant to the editor-in-chief of Dell Publishing. The first day on the job I got a taste of the blossoming love affair between celebrity and book publishing. Colonel Tom Parker, Elvis Presley’s manager, was calling on the phone.

I fell in love with book publishing. Yes, there was a lot of typing (ugh, white-out), answering phones, and making lunch reservations for my boss (the book I would have written was The Devil Wears Birkenstocks).

But there was also reading and evaluating manuscripts for publication and the constant search for exciting new writers. Somewhere I have a letter from singer-songwriter Suzanne Vega, whom I had contacted to see if she might be interested in doing a book for us. Her evocative lyrics suggested she might have other writing projects in mind. She wasn’t ready at the time, but I see she has since written two plays.

I was on my own by then, living in Brooklyn and getting to know the city that had seemed so far away when I was growing up. After about three years I became a junior editor, acquiring and editing my own books, mostly how-to and wellness. The transition took a little longer than usual because I did not go the traditional route—most women assistants moved up by becoming an editor on the romance novel line. But I was never drawn to the books myself (too focused on a happily-ever-after-ever conclusion) and wouldn’t have known what to do with a bodice ripper.

I wrote a few freelance pieces during this time and thought about going to graduate school. I loved book publishing but felt the writing bug more and more. I loved the city but yearned to see more of the country. In 1987 I got the push I probably needed. We were bought out by an international conglomerate, and I was laid off.

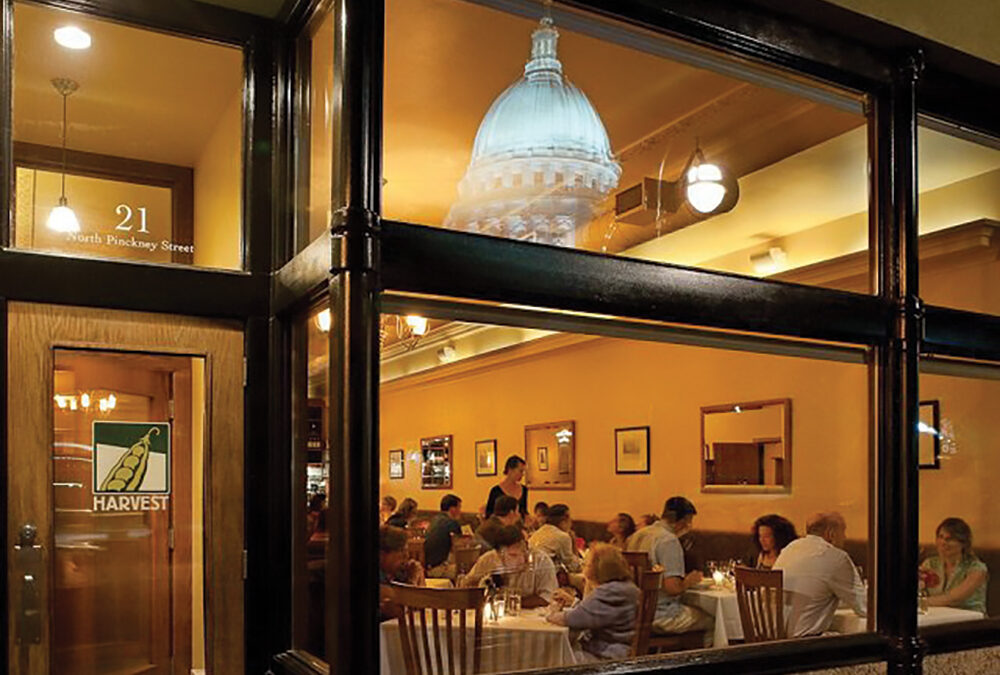

I applied to both public policy and journalism programs around the country. Had there been an internet at the time I might have known, from a three-second search, that some schools combined both in a single program. I did get into the Columbia Journalism School, the top J-school in the country, but ultimately decided on the Robert M. La Follette School of Public Affairs at U.W.-Madison. I wanted a better grounding in the subjects I intended to report on, and U.W. offered me a nice scholarship. My mom got her undergraduate degree from U.W.-Madison, and my cousin Miles was working in the med school at the time. I liked the feel of the town and its progressive politics. It seemed the time was right to explore my own Midwestern roots.

Finding a beat

I took just two courses in the journalism school—actually I took the same course, in-depth reporting, twice. In the second semester I wrote a story about how Wisconsin’s law banning abortion was still on the books and would become law if Roe v. Wade were ever overturned.

My professor suggested I submit it for publication to Isthmus. I got a call from news editor Bill Lueders, who was incredulous Wisconsin still had this law. It was true, I told him. And it’s true to this day.

After graduating, I paid the bills with project work at the city transportation department and freelance work. I did some daily stories for the Milwaukee Journal (it had not yet merged with the Sentinel) and contributed arts, features, and news stories to Isthmus. If I had a mentor along the way, the editors at Isthmus were it: Cathy Harding, Dean Robbins, and Bill.

I left Madison briefly to work at Rockford’s city magazine, but a couple of staff positions opened at Isthmus, and I was lucky to get one. I returned to Madison after a few months with a fresh appreciation for what our midsized city offers in terms of culture and quality of life—and acceptance. The “Jesus is Lord over Rockford” signs never sat well with me.

On staff at Isthmus, I felt that my gamble on a nontraditional path to journalism had paid off. I could write about things I was passionate about at a publication that valued long-form journalism, quality writing, and independent thinking. I was the features editor, but because of fluid lines between sections, I got to dig into some of the issues I had long sought to explore: gay and lesbian rights, reproductive health access, poverty, and welfare reform. Eventually I wanted to write more and edit less. I left Isthmus in 2000 to cover local government for The Capital Times.

While I missed some of the in-depth focus of Isthmus, I found a different kind of satisfaction in turning around breaking news quickly and following one beat closely. I followed the approach I learned while tracking legislation at Congressional Quarterly in Washington, D.C., where I had a summer internship during graduate school—context matters and should be included in stories large and small. It was also a pleasure to cover a city where true professionals were in charge of running government and were free to speak to the media. (Me to former City Comptroller Dean Brasser: “Uh, can you explain how Tax Incremental Financing works once again, please?”)

I eventually fashioned a social issues beat there before becoming an editor in 2008 when we ceased daily print publication. I returned to Isthmus in 2011 as news editor to write more and edit less (see a pattern here?) and became editor in 2014, just a few months after new owners bought the paper from its founder and sole owner.

I know there was trepidation in the community about whether Isthmus would maintain its news focus and in-depth reporting, but I hope we’ve since allayed those fears. Under our new ownership we completed a much-longed-for redesign of our print paper and website, Isthmus.com, beefed up our food and restaurant coverage, and added more multimedia reporting.

With my editorial duties, I might not be doing as much of my own writing as I would like, but there are other rewards, both creative and personal: steering coverage and story development; mentoring interns and newer writers; massaging final copy for publication.

My friend Linda noted that, when it comes to editing, I’m a natural: “You’re a perfectionist and a bit of a control freak.” Guilty as charged.

Putting down roots and stoking fires

When I moved to Madison, I thought I’d finish graduate school and move back to a larger city: New York; Washington, D.C.; or maybe Seattle, where my brother lived at the time.

Love kept me here after graduate school and, when I next considered moving for greater professional opportunity, I ultimately decided I was attached to Madison and wanted to stay.

And I’m now truly settled. I like a good, muddled Brandy Old Fashioned and the comfort of a Friday night fish fry. My partner, Rhonda, a Wisconsin native, and I are going on 10 years together; we share a house, our “dogter” Ursa and cat Max. We have great friends, our chosen family, with whom we share both the good and hard times. And I feel connected to the greater community, not on the outside as in my youth.

As for my career, I feel grateful that I survived the tsunami—and its aftershocks—that saw thousands of reporters and editors across the country lose their jobs when the economy tanked in 2008, and the journalism industry imploded. That doesn’t include those who have decided to leave on their own in recent years, tired of low wages, long hours, and the constant threat of future cuts. I’ve watched demoralized reporters lose their drive and motivation—what we call in the industry “fire in the belly.” It’s sad not just for journalists, but for our community and democracy, too.

Of course we’re now in a whole new era, where all media are lumped together and our worth, legitimacy, and credibility are questioned on a daily basis by, arguably, the most powerful man in the world. Incredibly, President Donald Trump recently tweeted that the media is “the enemy of the American people.”

The unparalleled attacks and falsehoods coming from Trump have pushed media to respond. I’ve been happy to see reporters like Chuck Todd and Anderson Cooper call out false statements and push back on obvious spin offered by Trump and his people. There has long been a tendency in mainstream media to rely on, in the interest of objectivity, “he said, she said,” journalism. The idea was to simply allow both sides to have their say, rather than to contest information that was patently false.

That was never the orientation of Isthmus. We always thought it was important to at least try to cut through the spin in order to get to the truth. It’s part of what drew me to the paper. And it’s something we remain keenly committed to.

The next four years promise to continue what is already a turbulent and transformative time for my industry. But I come from a long line of fighters. And I still love what I do. My work has always been more of a passion. I think about stories while on a bike ride and mull headliness in the shower. Perhaps that was my parents’ plan all along. They didn’t push, but maybe they had quiet faith—faith that I’d find my own way.

And I have.

0 Comments