One of M Adams’ most impactful childhood memories is of her grandmother teaching her how to properly dispose of soda cans.

Don’t crumple the metal. Thoroughly rinse out the can. Place it, along with any others, in a paper sack and leave it in an easy-to-reach spot in the back alley of her grandma’s home on Milwaukee’s north side. Neighborhood folks who were without homes or without enough income knew to come by and pick up the bag of cans and other scrap metal, to be dropped at the recycling center to make a bit of much-needed cash.

“It was a show of respect, she saw their dignity,” M explains. “My grandmother was phenomenal. She’s who I really learned the human rights framing from. She wasn’t a ‘movement’ person, just a simple woman, as she called herself. But she would always say, ‘It doesn’t make sense that people have to be homeless. It doesn’t make sense that police are out here killing people.’ And she showed that through her actions. The radical vision came to me from my grandmother.”

That radical vision is something M carries into her work as Co-Executive Director of Freedom, Inc., the Madison-based nonprofit at the forefront of many prominent protests of racial and gender-based injustices in and around the city. There’s a lot more to Freedom, Inc. than their public face, of course, and the same is true of M. Anyone who spends even a little bit of time listening to M speak or in conversation soon becomes keenly aware of the boundlessness of her heart, and the deeply thoughtful and tactical mind that keeps its rhythm.

Deep roots

M’s childhood neighborhood in Milwaukee was almost entirely Black and she attended mixed public schools. There were hardships at home and all around. Her mother was single and raising four kids on minimal income. M’s father has been in prison for most of her life, though she experienced his ‘presence’ through the many impacts of domestic violence. On top of that, their neighborhood lived under the constant specter of police harassment and violence.

“We had days where there wasn’t a lot of food, we had trouble with rent, we’d been evicted,” she remembers. Just as important, though, is that her community was one of “great love…great camaraderie. We helped each other out.”

“I still talk to many of the folks I grew up with. It was a really family forging time,” M says. It was that example of people coming together to help each other out in creative and loving ways—not always in the nuclear family format—that M credits with helping her develop her sense of self (including the queer notion of chosen families) and how she connected with others. “I get to benefit from radical queer imagination, and also of wise and sage Black cultures that are thousands of years old.”

Those early lessons left a lasting impression and helped instill within M the drive and dedication needed to do her life’s work. She earned a scholarship through the PEOPLE Program to attend UW-Madison and initially studied bacteriology. As a child, she’d sought ways to “change the world.” Becoming a doctor or scientist seemed then like the best options.

“Science helps us understand the world,” she says. “I wanted to use science to help people.”

Her experiences at the UW quickly showed her the more systemic issues at play in her life and that of her community. M became acutely aware of the differences between her and most of her classmates, from being one of the only Black students in her science courses to the access to resources others often took for granted. She recalls that almost everyone else had a computer or laptop, whereas she came to college writing papers by hand. “My mom made maybe $12–13,000 a year,” M says. “She did her best…we lived below the poverty line. I’d never owned a computer.”

“It wasn’t until I left Milwaukee that I really, in a very clear way, got to understand the systemic issues,” M explains. “I could easily point to stark differences between the opportunities I and my friends had growing up. Like access to the environment, for instance. In Milwaukee we never went to the lake, because it was where the white people live. But suddenly, at UW, my front door at the Elizabeth Waters dorm was right on the lake!”

The experience made the unfairness and inequalities crystal clear for M. “Why couldn’t my people live like that? We were not worse people, we were not bad people, we were people who deserved it, too. That really got me to understand systems in a different way.”

The problems on campus galvanized M into getting involved in several student organizations. She heard from friends in the social sciences about “terrible things” other students said in class and experienced for herself racist assumptions and microaggressions that still plague the campus.

Her campus activism “became my development as a social movement scientist,” M says. “I started thinking very critically about how you advance social change at a grassroots level to impact systems.

In that process I started to shift my thinking—if I want to help my folks, a doctor can only help one person at a time so maybe I should go into public health. But that doesn’t go as far as it could. Let me think about research, policy, and so on. But then I realized, a lot of these systems just need to be upended.”

The start of something new

It was shortly after UW, in 2008–09, that M first became aware of Freedom, Inc. and its founder, Kabzuag Vaj. A now defunct program called the Wisconsin Apprentice Organizing Project paid a small stipend and paired M with the relatively new organization for a six-month stint.

“I came in as this little intern who wanted to help build a queer youth of color program,” M says.

What was then called the Asian Freedom Project had initially begun in 1999 to focus on building knowledge and tackling gender-based violence in the Southeast Asian community of Madison’s Bayview neighborhood. Then a student at UW and a resident of Bayview, Kabzuag saw that college was affording her with life-changing experiences and information that largely wasn’t being made available to her community. She began teaching anything new she learned by setting up shop in a parking lot once a week.

The fledgling group organized (successfully) against everything from a proposed curfew ordinance to deportations.

“They also looked closely at what was happening inside their families, especially regarding gender-based violence,” explains M. “They started laying groundwork for a gender justice program for the Hmong community that still exists today.”

In 2003 the organization incorporated and the name changed to Freedom, Inc., with Kabzuag as its director. By the time M joined, they were operating out of a small office in the Bayview Community and mostly serving Hmong and other Southeast Asian women and girls, and LGBTQ young people with support groups. Growing pains were felt immediately.

“As the work expanded, a group of Black girls saw this programming for girls and wanted to come,” M says. “When they joined, it was an absolute disaster.”

Some of the difficulties were solvable, like language barriers and different styles of communication. Other differences were harder to overcome and negatively impacted both groups of people they were trying to serve.

“How the two groups were experiencing the same root issues looked so different,” M explains. “When it came to militarism, for instance, you have refugees and the children of refugees who experienced the Vietnam/American War, living under occupation, violence, and displacement. On the other hand, with the Black girls, they’d talked about how they might go into ROTC when they graduated high school because there weren’t a lot of other options for them. The military represents a way out for them because of a failed educational system. Some of them, too, had a father or uncle who was maybe a homeless veteran.”

Everything from how to discuss policing and how differences in gender are understood created schisms between the groups. Instead of continuing to try to force everyone to be together in all things, Freedom, Inc. instead adapted, developing their current slate of culturally specific programming.

“Instead of trying to say that it wasn’t different or to ignore those differences—which happens in a lot of multicultural spaces—we said let’s go into those differences,” M explains. “We developed…multiple conversations and spaces. Once we do that then we can build out a shared analysis.”

M credits Kabzuag for having “the wisdom to see that there was a need to approach ending violence for all communities.”

Since then, M first became the Director of Organizing and now the Co-Executive Director, where she’s frequently one of the prominent faces and voices for Freedom, Inc.’s community actions. The nonprofit has made a name for itself with pointed, tactical protests and organizing around everything from removing police from public schools to training youth of color in civic engagement and leadership. But it is through its radical model of culturally specific, community-based programs that has firmly entrenched Freedom, Inc. as one of Madison’s essential organizations.

Throughout, M has been a central figure, helping create and build the queer youth of color program begun when she was just an intern. She’s become a leading figure in the Take Back the Land movement, which works to block evictions and rehouse homeless people into foreclosed buildings. M has also presented in front of the United Nations for the Convention on Eliminating Racial Discrimination in 2014 and has authored and co-authored (for Our Lives and many other publications) several papers on Black community control of policing and how the killing of unarmed Black folks is a queer issue.

Laying a new foundation for justice

M is particularly excited for the potential of a building recently purchased on the south side to house Freedom, Inc.’s staff and programming.

The space represents a considerable expansion from their former offices on S. Park Street, where staff could only meet with people one at a time and there wasn’t enough room for their food pantry to operate more than one or two days a week (requiring that it be dismantled in between).

“We are creating a physical political home,” M says. “We’ve grown significantly. We have 18 full-time staff. The need is that great. We look forward to being able to run even more programs, to give our staff their own offices. So much of our work is people work: Safety planning with survivors, support for young or adult queer and trans folks. We need regular meeting spaces for leadership development work, for community celebrations and gatherings.”

M envisions a place where community members can plan and hold their own events, like “an elder who wants to lead a Zumba class,” art exhibitions, Pride proms, or bingo days for disabled elders. Seeing a lack of places for teens in Madison to go, they’re building it out as a safe space outside the home to congregate, learn, organize, and just be.

M hopes the new building will become a place for gay, queer, trans, and intersex people of color to meet up and socialize, too. “It’s always been, you gotta go to the bar,” she says. “Outside of that there isn’t much else. How do we have more spaces? We’re really building community. That doesn’t really exist right now for queer people of color in Madison.”

The that Freedom, Inc. will have the space to run multiple programs at the same time will be what has the greatest impact, M says. There are many voids to fill: They’re thinking about partnering with public health groups to provide diabetes checks and other pop-up services, expanding their food pantry, and holding dances and other events. They plan to do a lot of listening and to be in conversation with a range of people and groups.

“Community centers can’t be telling people what they need,” M muses. “It has to be an iterative process where the community co-creates it.”

Nationally beloved, locally suspect

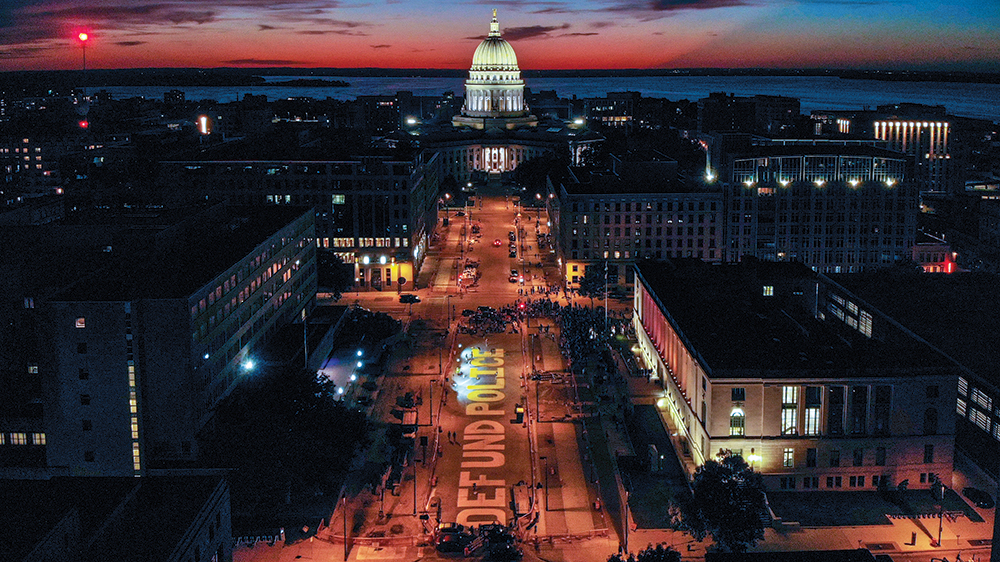

The recent explosion of visibility and awareness around racial justice issues has seen Freedom, Inc. and other small, grassroots organizations like Urban Triage and Free the 350 Bail Fund thrust more fully into the mainstream spotlight. Staff and volunteers with Freedom, Inc. have been helping organize and run many of the protest actions happening in Madison, day in and day out, as part of an effort to keep issues of racial justice at the forefront of people’s minds and push for the kind of change they’ve been fighting for over several years.

That visibility has always been a double-edged sword, M says. While many personal fundraisers on behalf of Freedom, Inc. have popped up in recent weeks and months, M explains that the majority of the group’s funding has and continues to come from national and state-level grants and donations. Locally? Not so much.

“A lot of times, the people who are creating the change are not beloved within the communities they’re serving. They’re directly challenging the people in that area,” M says. That’s certainly been clear in Madison, where Freedom, Inc. has been the frequent target of negative reporting and even racist political cartoons. The criticism isn’t just limited to self-described conservatives, either. Their calls for removing police from schools and for community control over policing have highlighted divisions within even Madison’s most liberal circles. M is clear-headed about why that is.

“We’re directly challenging those with resources right now and right here,” M says. “We’re saying something very directly to people: If you’re for queer people of color, for Black and brown people, you gotta dislodge this relationship with the police. That challenges people!”

A queer politic

M is hopeful, though, that this heightened moment will act as an invitation, “a nudge, even a direct challenge” to white folks—especially including white queer people—to get involved and support the work.

“White mainstream LGBTQ people are the beneficiaries of radical Black queer work,” she notes. “’The first Pride was a riot’ is not just a tagline, that’s a history. Black, brown, and trans women were experiencing police violence and fought back against it.”

“We have a plan to sustain the resistance and the vision,” M continues. “Opportunities like this can show a more comprehensive vision of who we are and what we’re about. Hopefully that garners more local support.”

It’s not always clear in how Freedom, Inc. is covered in local press, but they do consider themselves a queer organization and include many LGBTQI staff and volunteers. However, M is quick to point out that it isn’t their personal identities that makes Freedom, Inc. a queer entity.

“What makes us queer is our politic,” she says. “We have a radical way of seeing the world. A queer politic is about not seeking to become normative but seeking to be transformative. How we approach an issue is in a queer way.”

For instance, when they look at the LGBTQI people both running and using the food pantry, they’re thinking about how the entire food system could be reimagined to more fully serve all people. Is it fixing what’s already being done, or is it coming up with something entirely new?

“That is what it means for us to be queer,” M says. “It’s not just who my partner is, though that’s really important. But it’s also how I see the world and how I’m intervening in the world. That’s what ‘smash the binary’ is about. Smash the good vs. bad paradigm when we imagine safety. Break all different forms of binaries that we construct in society: Family vs. not, citizen vs. not, and so on.”

That spectrum approach is a testament to the wisdom M and others have taken from their elders and from each new generation.

“My grandmother really moved from a place of love and community,” M says. “She was the center of gravity for the family and really for our block. People knew that, if she had food, you had some, too. People knew that you could come over any time for a cool drink and a place to sit and talk. She was always very gentle.”

With her actions, her words, and the new building soon to be occupied by Freedom, Inc., M Adams is helping create that same safe place to land for those who most need it—to meet, to organize, and to imagine and build something anew.

0 Comments