A seemingly ordinary late-19th century house, just a short walk from the Capitol and State Street, holds a particularly notable place in history. It was that house that served as a nexus of political activities over nearly 14 years, from 1973 to 1987. Its inhabitants, young people who were self-identified as gay, lesbian or bisexual, were involved in progressive social movement politics and community activism, particularly in planning the advancement of civil liberties. That included the landmark Wisconsin gay rights bill, the first statewide law of its kind in the United States.

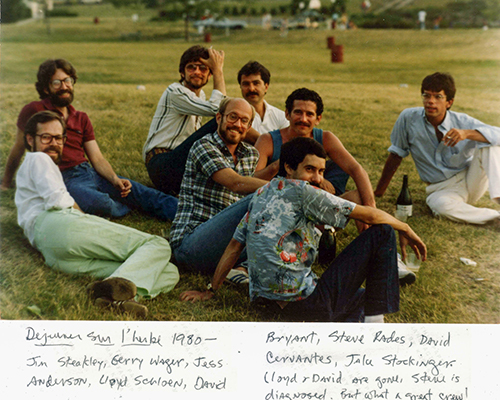

The house on West Gilman Street was also home to the Wuennenberg family, Martha Crawford, Steve LaVake, Jim Yeadon, David Clarenbach, Lynn Haanen, Earl Bricker, and many others. Its residents developed and ran political campaigns from the house, including Tammy Baldwin’s first run for Dane County Board supervisor. Simply known as 123 (one-two-three), its street address, the house’s important histories have only recently begun to be more widely known.

The Wuennenberg Family, 1973–1977

It all began when Carol and Rudi Wuennenberg bought the house in July 1973 for their college-age children and set into motion the development of a creative home environment of political activism.

A few years earlier, Carol and Rudi had moved to Madison from Wausau to be close to three of their five children who were to be enrolled at the University of Wisconsin. They wanted to live near the university and found a large Queen Anne-styled house at 504 Wisconsin Avenue, once the home of a Madison mayor and a Wisconsin governor.

Carol quickly became involved in the community: She worked on the James Madison Park masterplan, helped found the Fourth District Neighborhood Association, served as the Fourth District alder on the Madison Common Council (1974–1977) during Mayor Paul Soglin’s first administration, and served on the boards of Methodist Hospital and the Brooks Street YMCA. As a venue for her community work, the Wuennenberg home served as a salon for politically liberal progressives, as well as a refuge for young gay and lesbian folks finding their way, including two of their own daughters. Friends were free to come and go, and the doors were never locked.

Within two years, the social scene outgrew the house and the couple bought a new home at 123 West Gilman, with daughter Lora and her girlfriend Martha Crawford in mind. The young women established their own free-form salon and the house quickly became a hotbed of political activism for progressive, gay, lesbian, and other politically active friends. Martha and Lora supported the fledgling Women’s Transit Authority (WTA), a free nighttime rape prevention transit service for women, by holding volunteer meetings at the house. Lora was its first work-study student employee.

During the time they lived at the Gilman Street house, volunteer ranks grew from about 30 to 150 women. Sara Bringman, who lived with them, recalled, “The house was a scene of great activity in the emerging gay and lesbian scene in which we were all directly involved.”

The following year, Martha, and Lora’s new husband Steve LaVake, followed Carol’s lead and took on the tasks of reorganizing the Brooks Street YMCA to become locally controlled and free from the restrictions of the national charter. Renamed the University Y, it was used for housing and became home to the Women’s Transit Authority, the Lesbian Switchboard (a peer counseling group), the first public lesbian collective in Madison, and the collectively run vegetarian Main Course restaurant.

Jim Yeadon, 1976–1977

In September 1976 Carol encouraged her daughter Lisa’s friend Jim Yeadon to move in to 123, and shortly afterward, to join the Equal Opportunities Commission and to run for alder.

In 1975, along with the U.W. Gay Law Students Association and others, Yeadon had helped the Madison Equal Opportunities Commission rewrite its ordinance to include sexual orientation as a protected class, along with several other classes of people, to protect from discrimination in housing, employment, public accommodations, and access to city facilities. On March 11 of that year it was passed by the Madison Common Council and signed into law by Mayor Paul Soglin.

In recognition of his contributions, Yeadon was appointed to the EOC in October 1976 and reappointed in May 1977.

Also in October 1976, the Eighth District aldermanic seat became open. Yeadon ran for the seat for the balance of the term. Thirteen candidates applied for the seat. Yeadon won the vote. He came out the day after the special council election, ran for the seat in the general election in April 1977 as an out gay candidate, and easily won. At the age of 26 he became the first openly gay person elected in Wisconsin and the fourth in the United States. San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk was the fifth.

Yeadon lived at 123 until September 1977. While on the Madison Common Council in 1978, Yeadon quashed a repeal of the Madison non-discrimination ordinance he’d helped forge. He became known as one of the most knowledgeable people in the country on municipal gay rights laws. A few weeks before his term was up, he resigned from the common council position to pursue other endeavors.

Jim Yeadon met David Clarenbach at one of the Wuennenberg parties at 123, though knew of him in political circles previously. They became companions over a couple of years and shared stories of their individual work in each of their political realms. They collaborated several times in joint appearances in media on civil rights and gay rights issues and developed a personal relationship.

In September 1977, Yeadon learned that the Wuennenbergs wished to sell 123 and told David, who bought it without hesitation.

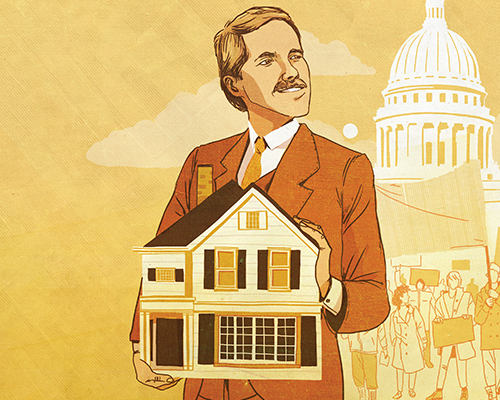

David Clarenbach, 1977–1982

David Clarenbach lived at 123 West Gilman Street from September 1977 and until June 1982. During his time there, as the 78th District State Assembly Representative he was primarily responsible for the passage of the first state law in the country (1982) prohibiting discrimination in employment, housing, and public accommodations on the basis of sexual orientation. It was Assembly Bill 70, dubbed the Wisconsin Gay Rights bill. While living there he also undertook the majority of the legislative work that culminated in the signing into law of the Wisconsin Consenting Adults bill, in May 1983. He worked to further legislation while at home, particularly evenings and weekends, when most of his constituents would contact him with a phone line forwarded from his office.

Born in St. Louis, Missouri in 1953 and raised in Madison, David came from a family of political activism. A principal influence on his life was his mother, Kathryn (Kay) Clarenbach, a nationally prominent figure in the women’s movement and a co-founder of the National Organization for Women (NOW). David’s father Henry Clarenbach had been a Eugene McCarthy delegate to the 1968 Democratic Convention.

Early among the friends who influenced the political work of David Clarenbach was Dick Wagner. While Clarenbach was in high school they met while participating in anti-Vietnam war meetings on campus. In the early 1970s, Wagner was involved in many historic preservation projects in the Mansion Hill neighborhood, from developing Period Garden Park to securing the location for Gates of Heaven Synagogue, and planning for James Madison Park, where Clarenbach worked with him again. Wagner was a model of civic leadership and they became fast friends.

In 1973–74, Clarenbach shared Wagner’s apartment in the brick coach house at 136 E. Gorham. Wagner became a mentor for Clarenbach, who ran for re-election to the County Board in the spring of 1974 and months later ran for the State Assembly. That fall Wagner moved to Jenifer Street.

Clarenbach’s Political Career

In 1971, when David Clarenbach first moved downtown and sought elected office, Fourth District Alderman Dennis McGilligan advised him to chair the neighborhood park planning committee. He then suggested that David run for the County Board of Supervisors. David announced his candidacy in the winter of 1972 and won the primary and the general elections. He became the first 18-year-old in the state to be elected following the passage of the 26th Amendment to the Constitution that permitted 18-year-olds to vote and to hold public office.

In 1974 at age 21, concurrent with his position on the Dane County Board, he also became an interim City of Madison alder for a short time. Not satisfied with county work alone, in the fall of 1974, he ran for the 78th Wisconsin State Assembly seat. He won the election and began what was to be the first of nine terms as a Wisconsin State Representative.

During his early years in politics, Dick Wagner wrote David’s first campaign materials that stated positions on expanding civil rights including sexual preference (later, appropriately called sexual orientation) and abolishing laws that regulated victimless crimes and private morality. These positions were patterned after those that Wagner used in his own 1974 aldermanic campaign for the 2nd District.

Beginning 1975, Clarenbach collaborated with Lloyd Barbee of Milwaukee, an important civil rights leader, and, at the time, the only African-American representative in the Assembly (1965–1977). Previously, Barbee had authored legislation on sexuality to repeal obscenity, abortion, and prostitution laws, and to allow same-sex marriage. Barbee didn’t have success in their passage, but succeeded in pushing the boundaries in an effort to educate legislators and the public. Barbee had written and promoted ending sexual criminalization and discrimination since 1967. He saw in Clarenbach a young firebrand with whom he could further the cause. Clarenbach accepted Barbee as a mentor and, following Barbee’s departure from the Assembly in 1977, David sought to continue the work they had planned—to undertake parallel efforts of decriminalizing consensual sexual behaviors and end discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Soon after Clarenbach moved into 123, he planned to move a consenting adults bill first, since it seemed to be more easily supportable. It would decriminalize cohabitation, sex outside of marriage, and homosexual behavior. To promote his efforts in 1977, he employed the terms “consenting adults,” “sexual privacy” and “victimless crimes” to bring legislators and the public to support broad reforms that would affect many people while pairing them with related non-discrimination reforms that would affect fewer people.

In his introduction of the Consenting Adults legislation in the Assembly Session of 1979, David stated, “The change this bill presents is one of the most basic principles of our country—the right of protection against unwarranted interference by the government in our private lives.” As the prime sponsor, he reintroduced legislation to decriminalize private behavior between consenting adults. The effort gained essential ground and growing support of Republicans and Democrats alike.

David found an enthusiastic collaborator in Leon Rouse, a University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee student who helped coordinate the support of religious leaders for the non-discrimination bill as a human rights issue, rather than as a gay rights issue. Rouse garnered the support of Catholic Archbishop Rembert Weakland of the Milwaukee Archdiocese, who influenced the decisions of Catholic leaders, congregants, and legislators throughout the state and facilitated passage of a similar Milwaukee ordinance.

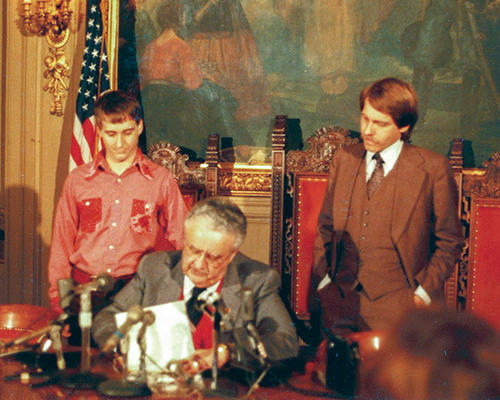

David used the Consenting Adults bill to count the votes he felt would be similar for the non-discrimination bill, AB70, and knew there might be only one opportunity to vote on it. In the fall of 1981, it passed the Assembly; it passed in the Senate on February 16, 1982, and the Assembly concurred; and on February 25, 1982, Republican Governor Lee Dreyfus signed AB70 into law as Chapter 112 of Wisconsin laws with Rouse and Clarenbach at his side. As a result, “sexual orientation” was added to the list of non-discrimination categories in Wisconsin’s laws: political or religious opinion, or affiliation, age, sex, handicap, race, color, national origin, and ancestry.

“The question wasn’t whether homosexuality was right or wrong,” David said. “The question was whether bigotry or discrimination could be tolerated against any group in our society. And when that was posed, the answer was no.” It would be another seven years before the second state in the nation, Massachusetts, would enact a similar non-discrimination law. Presently, there are 22 states that have similar non-discrimination laws based on sexual orientation.

The Consenting Adults bill was next. Twenty-five other states had such laws. The bill had taken much heat over the issues surrounding legislating morality. Initially authored by Clarenbach and Barbee in 1975, it was reintroduced and modified in five legislative sessions. The Consenting Adults bill made its way through the 1983–1984 session as AB250. With Democrats in the majority, the bill passed in the Assembly on April 21, 1983, in the Senate on May 3, 1983, and was signed into law by Governor Anthony Earl on May 6, 1983. “I think it reaffirms the willingness of the Legislature to endorse privacy rights,” David stated.

He noted that two later bills owed their passage to the bipartisan support of the 1982 non-discrimination bill. In 1985, David lead the effort to pass a State Bill of Rights for people with AIDS and HIV infection to protect people from being denied insurance coverage and medical treatment and to protect privacy against stigmatization. In 1988, he lead the effort to pass the Wisconsin’s Hate Crimes Act, partly as a preventative measure and to better respond to crimes that were often ignored or not prosecuted.

Months later, redistricting forced David to move from 123 and, for the next five years, leased it to Eighth District Dane County Supervisor Lynn Haanen and friends. He believed that Lynn would continue the same kind of synergy in the house with her political activities.

The importance of place

“Wisconsin was at the forefront all along in advancing not just the political protections and legal protections, but the social movement which has resulted today in some reforms and some advancements that none of us thought would be possible even within our lifetime,” David noted.

He attributes the physical space afforded to the movement at the house as a crucial factor in its successes. “I am convinced that those would not have happened if we hadn’t had the physical environment, the place in time, to congregate a community of interest and a wide range of communities of interest,” he said. “Not just people who were gay or lesbian, but people who were committed to the cause, the civil libertarians, the religious leaders, even Republicans in the Legislature all contributed to success.

“There’s no magic wand, but I have to say that without 123 West Gilman, these things would not have been accomplished, and that right there in my view qualifies for a special designation for 123 West Gilman,” David added.

123: A Home for Civil Rights Activists, 1982–1987

Lynn Haanen, 1982–1986: Lynn Haanen was raised in Chippewa Falls, came to Madison to study journalism, then switched to political science. She got a job as a page in the Capitol, then worked in Washington, D.C. for U.S. Senator Gaylord Nelson. She returned to Madison in 1977 and worked in the Capitol as an aid before taking a job with the Women’s Transit Authority. She considered herself a socialist and began her public service when she was drafted by friends for the Eighth District seat on the Dane County Board of Supervisors in 1979, and was appointed by Mary Louise Symon. The youngest of the 41-member board, she easily won election in 1980, 1982, and1984. She earned the respect of conservatives and liberals alike in her work on the County Board’s Finance Committee and as Chair of the Board of Public Welfare that oversaw the work of Dane County Social Services.

In August 1980, prior to living at 123, Haanen participated in the Dane County Board of Supervisors passage of a change in the county’s Affirmative Action Ordinance to prohibit discrimination based on sexual orientation, along with supervisors Judith Blank, Dick Wagner, and Larry Gleason.

In late 1983, County Supervisors Haanen, Wagner, and Kathleen Nichols co-sponsored a resolution supporting a grant application for the study of the impact of AIDS for the University of Wisconsin Medical School and shepherded it through the Dane County Board of Health, an early measure in Wisconsin. At the time, there were 1,000 cases nationwide, and none yet reported in Wisconsin.

During Lynn Haanen’s time at 123, she hosted San Francisco gay rights activist Harry Britt, and worked in constituent relations in Gov. Tony Earl’s office and met Earl Bricker and Tammy Baldwin. Lynn also hosted myriad campaign efforts, including her own and those of David Clarenbach, Bob Kastenmeier, Eighth District Alder Anne Monks, Governor Tony Earl’s re-election, and Tammy Baldwin’s first run for Dane County Board supervisor. Political meetings and discussions were often held throughout the house, frequently in the “bull pen,” the living room where ideas became campaign strategies, according to Clarenbach.

Earl Bricker: In late 1983, Earl Bricker joined Haanen at 123. He moved to Madison in 1978, worked for the Democratic Party and was an executive board member of The United. In August, 1985, mid-way into Governor Tony Earl’s administration, Bricker was appointed to a position in the Constituent Relations section of the governor’s office where he staffed the Governor’s Council on Lesbian and Gay Issues. The volunteer council’s task was to assist and advise the governor and state agencies “on measures to eliminate discrimination against and victimization of lesbians and gays in Wisconsin.” Bricker also recruited gays and lesbians for gubernatorial appointments to some of the 156 governmental bodies. He was sometimes assisted in the office by Lynn Haanen.

In about 1986, Bricker moved from 123. He was elected in 1988 to the Ninth District seat of the County Board of Supervisors and when he stepped down mid-term in 1991, he helped launch Mark Pocan’s career in politics as a Dane County Supervisor.

Anne Monks: While working in 1978–80 as a community planner in the City of Madison Plan Department, Anne Monks completed her master’s degree from the School of Business of the University of Wisconsin-Madison under Professor James Graaskamp. During that time, Anne met Lynn Haanen and they became fast friends, developed a personal relationship—a partnership followed by a life-long friendship.

As a resident of the neighborhood, Anne helped establish the Langdon Area Neighborhood Association, was an organizer of the Madison Mutual Housing Association, and served on the board of the Madison Community Development Corporation. She was elected alder of the Eighth District in November 1980 in a special election, and elected again the following April. During her nearly three-term tenure she served on the Board of Estimates and as Council President for a year. She pushed to get the Langdon area listed on the National Register of Historic Places. She left in mid-1986, when she took a job in Washington, D.C.

Tammy Baldwin: In the fall of 1985, when Lynn Haanen decided not to run again for the county board, Tammy Baldwin approached her to run for her seat. They had met while Tammy was serving an internship in the office of Governor Anthony Earl, under the supervision of Roberta Gassman in 1984–85. Haanen felt Baldwin was a perfect match for the district, so hosted her first fundraiser at 123 in December 1985. Baldwin was readily elected to the Dane County Board of Supervisors in April 1986. Baldwin was drafted by Alder Ann Monks to replace her on the council that summer and was appointed by the Madison Common Council to fill the vacancy until the general election in November 1986.

In 1992, Baldwin ran for and won David Clarenbach’s former seat in the 78th State Assembly District when Clarenbach opted out of an Assembly race to run for Congress. Baldwin became the first openly LGBTQ member to be elected and to serve in the Wisconsin state legislature. In 1998, she became Wisconsin’s first woman and the nation’s the first out LGBTQ non-incumbent to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. She was elected to the United States Senate in 2012, becoming Wisconsin’s first female U.S. Senator and that body’s first openly gay member.

The Local Community Impact Due To LGBTQ Civil Rights Achievements

“There was an elation” shared by gay and lesbian activists at the time of AB70, the Gay Rights Bill’s passage. “It just really gave people a sense we could be part of this society in a larger way,” according to Dick Wagner. As a result, volunteerism and support of gay organizations flourished. The sense of community health and wellbeing grew beyond what could have only been imagined just a few years earlier.

The subsequent election of Governor Tony Earl and his support for LGBTQ communities emboldened a groundswell of change. The flurry of political and community interaction among the residents of 123 was indicative of the new optimism manifested in political activity and in the development of new community institutions such as the founding of OUT! newspaper and several LGBTQ social and service organizations.

The extraordinary setting that was 123 came to a quiet end in June 1987, when David Clarenbach sold the house. During the prior 14 years, the house had been home to several politically engaged people who helped set the tone for the future of the gay and lesbian community locally, the progressive community and civil rights statewide and nationally.

Making a landmark, hitting a wall

A nomination of the Clarenbach House as a potential Landmark designation by the Madison Landmarks Commission was submitted in early November 2017 by Gary Tipler. A staff review is underway, according to Madison historic preservation planner Amy Scanlon. A Landmarks Commission public hearing is scheduled for March 19. The commission’s recommendation will then be submitted to the Madison Common Council for a decision.

Margaret Watson, the CEO for Steve Brown Apartments which owns the Clarenbach House, in December stated that the company hadn’t taken an official position. However, Watson called for a legislative committee to address “owners’ consent” for designation of historic properties as part of a law being considered in January. On January 3, Watson testified before the Housing and Real Estate Committee Hearing that “owner consent” for the landmark designation of historic properties was necessary and needed to be addressed, while commenting on a proposed bill on rental properties and tenant law. Madison and numerous other municipalities presently do not require owner consent for designation, nor for other aspects of planning administration.

A new proposed “owners’ consent” legislative hearing for Senate Bill 800 was announced the morning of February 13 and held on the afternoon of February 14 before the Committee on Insurance, Financial Services, Constitution and Federalism. If passed, the new language could prevent the local designation of the Clarenbach House and innumerable other buildings.

Keep up-to-date with the Clarenbach House Project on Facebook.

0 Comments