If you’d told Kathy Flores five years ago that she’d be spending most of her days at home, resting, tending to her small garden, spending time with her daughters and grandkids, and wrangling a naughty but adorable rescue pup, she probably wouldn’t have believed it.

“Slowing down” was not part of Kathy’s vocabulary or work ethic for most of her life. The Appleton resident and longtime advocate and activist has become a familiar and trusted face in both LGBTQ and intimate partner/domestic violence (IPV) circles in Wisconsin over the past two decades. During that time, she’s worn many hats, helped create vital policies and training to better serve survivors and LGBTQ people generally, put her neck out to fight for equal rights, and driven more miles across the state than most.

These days, however, Kathy’s mental and physical health have told her in no uncertain terms that the time has come to embrace a more relaxed pace. The transition hasn’t always been easy, but she admits that it’s been a good one.

“My first instinct is to act,” Kathy says during an interview over her kitchen table on a sunny summer day. “But I needed to lay down my sword. I’m still involved when and how I can be, but it’s more through providing emotional support and advice to those still in the field.”

Allowing for rest and small moments of joy have become her guiding principles in this new chapter of life. Kathy stepped down as the anti-violence program director for Diverse & Resilient this spring, after serving in that role for seven years. It was, she says, a decision her body made for her. Worsening symptoms from MS diagnosed in 2007, plus other health issues, pushed her to exhaustion.

Instead of working 70- or 80-hour weeks, driving across the state to work with organizers and survivors, the mom of three adult daughters is spending the time with them that she says she largely missed as a young, single, working mother. And there’s Katie the dog to keep up with, too, an affectionate and squirmy rescue Yorkie taken in by Kathy and her spouse, Zephyr.

There’s plenty to reflect on and be proud of, in addition to looking forward to what comes next. And Kathy emphasizes the importance of supporting the next generation of leadership.

“It’s time for a younger, browner, blacker, more queer and trans generation to lead,” she says. “We all better be thinking about succession.”

The Biggest Allies

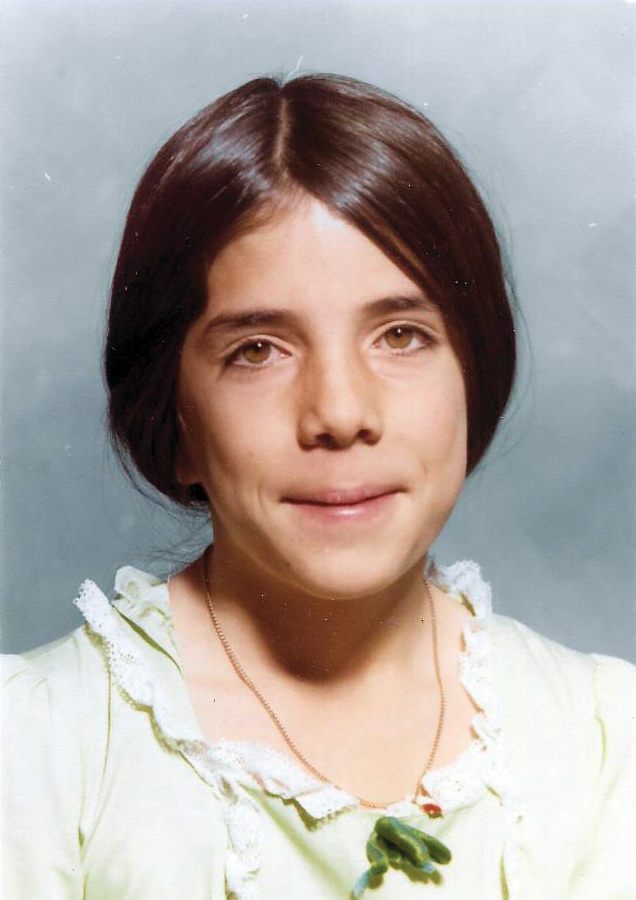

Born in Montana to a white dad and Mexican mother, Kathy found her early life marked by change. The family moved first to Texas, then to southern California where her father “followed the call” and began his ministry as an independent fundamentalist Baptist, and finally to Michigan after her father “followed the call” to lead his own church and eventually Christian School.

“It was because he said the other Baptists were too liberal, including the Southern Baptists,” she notes wryly.

Kathy dutifully met her father’s expectations, embracing his evangelical faith and, she admits ruefully now, parroting the same hellfire and brimstone lines and participating in book and record-burning events led by his churches. The same fervor and dedication she’d later bring to her far more progressive advocacy work was apparent in those early days, she says. But cracks in her adherence to her father’s ideology appeared early.

“I tried out for and got onto the cheerleading squad in high school,” Kathy remembers, “and was promptly kicked off for refusing to sign the purity pledge. For me, it had nothing to do with sex, but was because I didn’t want to go along with the ban on listening to rock and roll.”

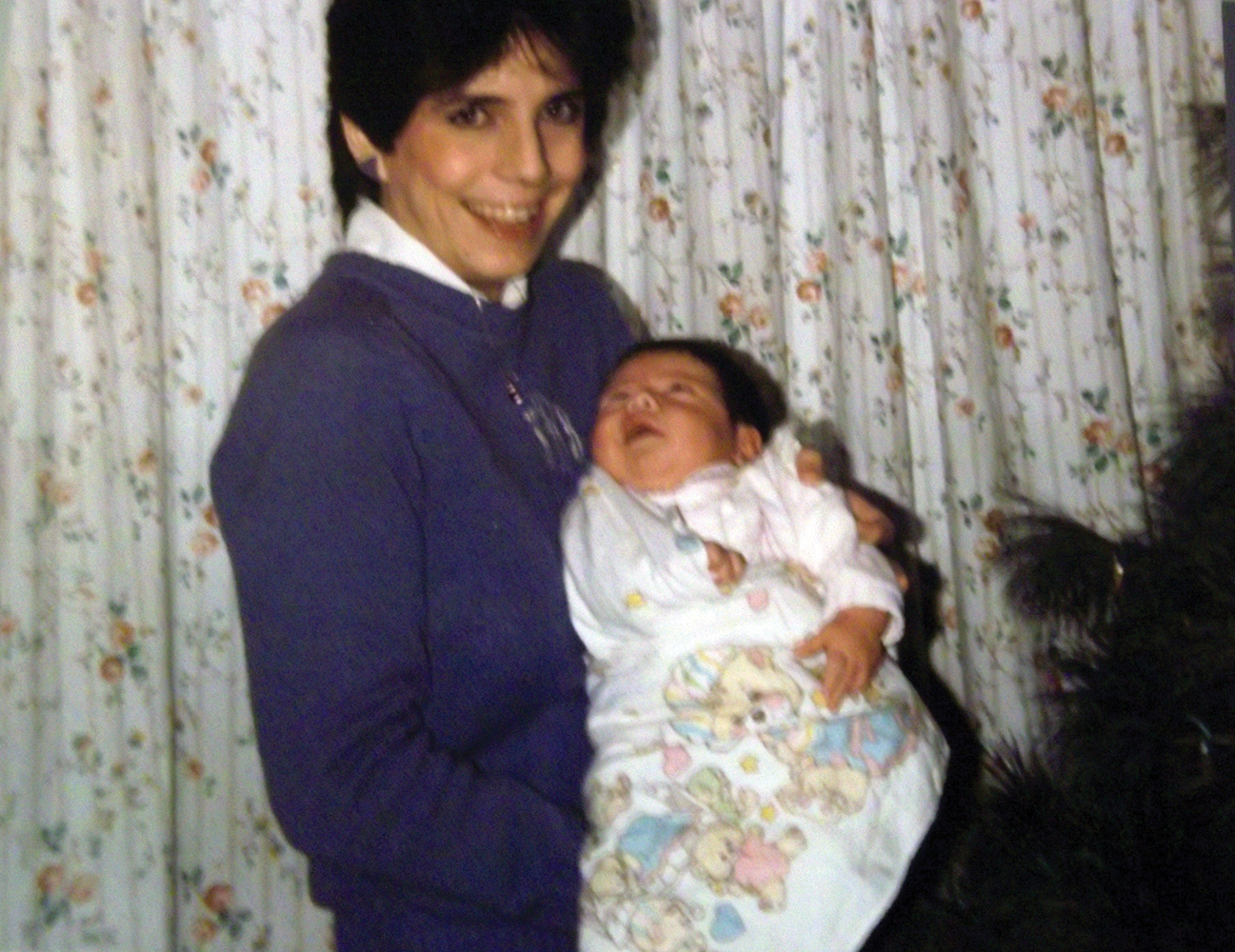

She also had inklings of her own queerness early on. There was a first kiss with a best friend when she was 10 years old, something she later tearfully repented for at one of countless tent revivals. It was, her father said, the “only sin called an abomination in the Bible” and, therefore, the very worst. Unforgivable, even. Kathy internalized a deep homophobia and fear that would see her through three marriages to men, two of whom ended up being abusive. The first was a boy she began dating at 12, only to end up pregnant at 17.

“First of all I wasn’t allowed to have sex,” Kathy says, “but then my mom had the nerve to say, ‘Well didn’t you use birth control?’” Of course, it had never been discussed.

She worked as a waitress and struggled to make ends meet, and by the time she got out of her first marriage at 21, Kathy decided it was time to go back to school and start work on building a career that could support her and her children. She went to Fox Valley Technical College and came out with a job at the Kimberly Clark Corporation doing administrative work. It was there that she first joined what were then called employee networks (now employee resource groups), including the Gay, Latin American, and African American Networks. It was, she says, an eye-opening experience.

“I was most heavily involved in the African American Network. I initially showed up because they needed a secretary,” she remembers. “So I walked into the first meeting and it’s me, sitting at a table with Black folks, and they’re wondering what the heck I’m doing there. And I’m like, ‘I wanna help!’ But I didn’t have a clue about race relations.”

Kathy credits the Black women in the group for kickstarting her anti-racist and DEI journey. She acknowledges that they took a chance on a young, naive, white-presenting person with a lot of her own internalized racism. The women became dear friends over the years that followed.

“My entire view on race and racism is shaped by Black women. Dr. Sabrina Robbins and Dr. Bola Delano-Oriaran in particular taught me how to be an ally to Black people. And they consider themselves church ladies, they weren’t always knowledgeable on LGBTQ issues, but I stayed with them because they stayed with me, and now they are my allies. They were able to help me learn about Blackness, and later on I was able to help them learn about queerness. If I hadn’t had them take me under their wing I don’t know that I would have gotten it. They took the time to be like, ‘You’re fucking up.’ That’s a gift.”

The mentorship and the community helped open her eyes to what Kathy saw was serious racial discrimination in the Fox Valley. While they worked to improve recruitment processes at Kimberly Clark, she noted how little was being done on retention.

“We’re not doing anything to make people’s lives better once they get here,” she reflects. “And even if we do that within the corporation, we have this whole community to deal with.”

It prompted her to get involved in community activism, volunteering to do work around anti-racism and DEI, including on LGBTQ issues.

“I was probably the biggest ‘straight ally,’ Kathy says with a laugh. “In fact, I had a lesbian friend who, when I finally came out years later, said, ‘Oh no, we lost our biggest straight ally!’”

It was just the beginning of what would become her life’s work.

Learning Along the Way

It was also during her stint at technical college that Kathy first got interested in studying and then speaking up about domestic violence. She had experienced it herself. After volunteering for a sexual abuse support group, in 2000 Kathy became the first director of Harmony Cafe in Appleton, a peaceful place for celebrating diversity. Even before the organization had its own physical space, she helped cultivate a safe and supportive environment for queer and transgender young people to hang out and have art and music-related events.

Shortly thereafter, in 2002, she joined a local program providing shelter and support for survivors of domestic abuse. It was at this shelter she met Beth Schnorr, her boss and someone who became a beloved mentor.

“Beth taught me how to put survivors at the center of all of our work within the DV movement,” says Kathy. “Many long-term DV/SA directors and advocates can get smug in their knowledge of violence, but Beth instilled in me that survivors, not advocates or academics, are the experts on their lives. Beth was very supportive of the LGBTQ IPV work I did in Appleton and throughout the state. She sat in on community meetings and showed up at LGBTQ rallies and presentations to show support from the top of the organization. I doubt there would be a Diverse & Resilient IVP program without the influence of Beth.”

In the domestic and sexual violence movement, Kathy was able to bring her DEI lens to the work: She noted that there were no services for transgender women or gay men dealing with intimate partner violence. There was little awareness generally at the time about IPV among queer and trans people, and Kathy knew something needed to be done. She wrote one of the first model policies for shelters to help them offer competent care for the LGBTQ+ community, followed by helping to form a committee that developed outreach and training for shelters across the state interested in the work.

There was plenty of learning from mistakes and an evolution of her own understanding of gender and sexuality along the way, Kathy says.

“The original model policy is, in retrospect, pretty cringy,” she notes. “It was a start, but at the time we wrote things like, ‘If someone identifies as their gender 24 hours a day then they belong in the shelter that corresponds.’ And I quickly learned that, especially for many of the trans women who came to us, it wasn’t safe for them to be out at work or at home. It was impossible for them to meet that expectation.”

She quickly realized that true progress could only be made by listening to and centering the people most impacted.

Furthering that work, Kathy founded the Fox Valley LGBTQ Anti-Violence Project in collaboration with Harbor House Domestic Abuse Programs, Christine Ann Domestic Abuse Services, Reach Counseling, and the Sexual Assault Crisis Center.

Long days of driving across the state to lead training for various shelters and IPV groups followed. Kathy shakes her head when she thinks about the time and energy she used to put into the work, but she wouldn’t have had it any other way.

A Constitutional Collision

It was during this era that what Kathy refers to as The Collision happened. It was 2004 and Harbor House needed their website updated.

“Along comes this little volunteer wearing overalls and smelling of patchouli and sawdust,” Kathy remembers with a knowing smile. “My attraction went through the roof. This person came in and started calling me ‘boss lady.’ That’s how I came out. It was because of Zephyr.”

Kathy was just getting out of a straight marriage and Zephyr had just gotten sober. The timing wasn’t perfect but the sparks were very real. Six weeks after getting together, they decided to step back and become ‘just friends’ instead. That lasted two years before they coupled back up.

Nearly 20 years later, Kathy and Zephyr have weathered a wide variety of stormy and calm seas together. There was the onset of Kathy’s MS symptoms just three months into their relationship, and five months into it, Kathy was diagnosed with an aneurysm, followed by numerous doctor and hospital visits to deal with that and a pulmonary embolism developed after a routine hysterectomy. Before all of this medical drama was the first date that should have derailed the whole relationship.

“We went to see the movie ‘Troy.’ I didn’t know at the time that Zephyr couldn’t handle much violence. And then afterwards we were at dinner, and I didn’t know how to be with anyone other than cis men, didn’t know how to give compliments, and Zephyr at the time would have used ‘genderqueer’ or ‘genderfuck’ to describe themselves. But I said, ‘You have such nice dainty hands.’ And Zephyr appeared offended, but I didn’t get it. I was clueless.”

She is, in retrospect, amazed that she got a second date, let alone the long-term relationship that has been an anchor for her ever since. Even getting to that point had been a hard-won victory after years spent working through religious conditioning, bad marriages, and even worse professional advice.

“When I met my third husband—a sweetheart, he was a great guy—when he proposed to me I said, ‘I don’t know if I should get married because I think I’m a lesbian.’ We were only married for five years. During that time we went to see a therapist—who’s still practicing today—and they wrote it off by saying, ‘Well, Kathy just loves things that are ‘taboo’ and being a lesbian is taboo.’”

The therapist recommended incorporating lesbian pornography into their relationship. Needless to say, that didn’t save the marriage.

With Zephyr, everything felt right but the world threw different challenges at them. For the first time, Kathy was facing down discrimination in the form of homophobia—both on the personal and political level. Medical discrimination led her to realize that, despite having a living will, there was no legal guarantee that Zephyr would be allowed access to Kathy during a medical emergency, nor would Kathy be able to prevent blood family from making decisions about arrangements if she were to die. It was well before gay marriage was nationally legalized.

In 2009, then Governor Jim Doyle added the domestic partnership registry in his budget. Seeing the chance to make her voice heard and emphasize the importance of such rights, Kathy wrote a letter of support to Doyle and copied the LGBTQ advocacy organization Fair Wisconsin on the missive. It was how she found herself testifying before the Joint Finance Committee, which was broadcast on local television and radio stations. Around this time, Kathy drove home from work to find that anti-LGBTQ pamphlets had been left blanketing her neighborhood.

In response, Kathy wrote to friends and asked them to donate to Fair Wisconsin in the name of the hate group responsible for the pamphlets. The actions won the couple a Leadership Award from Fair Wisconsin. When the registry was later challenged in court by perpetual anti-LGBTQ gadfly Juliane Appling and her Wisconsin Family Action hate group, Kathy and Zephyr stepped up as one of five couples who served as intervening defenders in the case. The registry was ruled constitutional in 2011, thanks in part to their efforts.

Not everything has been a political whirlwind in their relationship, though. Kathy and Zephyr have settled into the role of grandparents more than ever. Zephyr, who in the beginning of their relationship was pretty clear they never wanted children, has become an “absolutely adorable, loving grandparent” to their four grandchildren, Kathy says.

The two can also frequently be found tooling around their neighborhood in Appleton—Kathy on her mobility scooter, Zephyr on their bike. They stop at local parks and restaurants, determined to enjoy every moment of nice weather they’re afforded.

Since 2014, Kathy says, they’ve been practicing daily gratitude with each other and have yet to miss a day to tell the other something that they are grateful for in the other.

Pushing the Paradigm

The year 2009 proved to be big for Kathy all around. Feeling like it was time for professional change, Kathy was looking for a sign. It came when a work vision board she’d created suddenly fell off the wall and crashed to the ground. And then a member of the mayor’s African American Advisory Committee called and told her about a new job with the City of Appleton that seemed like a perfect fit.

Then-mayor Tim Hanna was looking to hire someone to become the city’s next Diversity and Inclusion Coordinator. During the hiring hearing, he noted that he wanted “someone to challenge the status quo.” Kathy knew she was right for the job.

“Everybody told me, ‘He’s a Republican!’” she remembers. “I have yet to see evidence of that. Everything I brought to him he said yes, go do it.” That ended up including things like refugee resettlement, protections for transgender people in housing and employment, and domestic partner benefits for city employees. But while all of those initiatives eventually passed into law and/or action, they didn’t come without a fight.

“I was dealing with all of my health issues and a very hostile environment for being a queer diversity and inclusion coordinator,” Kathy says. Her job was threatened three separate times, as the city council debated whether or not to keep it during budget hearings. Every time she did anything the conservatives on the council didn’t like, they let her know it.

“I was under fire all the time. I helped lead some of the work around passing domestic partner protections within the workplace, and that battle got my job on the chopping block. One alderperson, Mike Smith, was overheard saying, ‘Well this position’s gotten a little too gay.’”

The next battle resulted from something Kathy had intended as an easy win for the council. Local businesses had been requesting some kind of official campaign around inclusion. Kathy worked to create one. It would have made available stickers for businesses to put in windows simply to indicate that they were safe spaces for and inclusive of all people.

“You would have thought I was asking them to put a Satanic symbol up,” Kathy says of the reaction she got from the council. “They tore me to shreds. I was so naive. This was in 2011, it was my first time really going before the council and having to answer questions. I wasn’t prepared.”

The campaign never made it out of committee.

Conversely, her work with Fair Wisconsin to make Appleton the third city in the state to add protections for transgender people flew largely under the radar. The city council passed housing and employment protections for gender identity with little fuss, especially when compared to the outrage that cropped up around the domestic partner benefits.

“It was so absurd,” Kathy adds. “In those years, three times, we had the whole community show up at the budget debates, and I always fought to save the position. We always won. But it was so political, and it was because we were queer and we were doing queer work. I think it was probably the most visible position I’ve ever been in and there’s a point where I probably had 30 open records requests trying to prove my big gay agenda. And I’m like, I’m not lying about it! I have a gay agenda. I also have a pro-immigrant agenda. I’m the Diversity Coordinator! I’m pro-marginalized people.”

After supporting local Black Lives Matter protests on her own time as a private citizen, Kathy says, the city’s Human Resources and Police Departments essentially black-listed her. They went behind her back to hire an outside consultant to do DEI training so that Kathy wasn’t the one leading it. She couldn’t get a raise. Then, the Pulse shooting happened.

“I just said, ‘fuck everything.’” After years spent bending over backwards to keep her LGBTQ activism and her job separate, Kathy organized a vigil while on work time.

“A lot of the work we were doing [at the city], it felt like it was to check a box and to make white people feel good. That’s not what I’m about,” she says.

Unanticipated Need

Intersectionality, anti-racism, and community care are at the core of all Kathy’s work. It’s what ultimately drew her to take a job as the anti-violence coordinator at Diverse & Resilient in 2016. Initially, her role was focused solely on starting a statewide LGBTQ “warm line” for survivors. It had her traveling the state to find pockets of LGBTQ people organizing, “unicorns in the woods,” as she calls them.

It became very clear very quickly that there was much more need than anticipated. In 2018, she applied for and got a grant to help open a second D&R office in Appleton and Milwaukee. Between the Appleton and Milwaukee offices, there are six staff members serving survivors of violence, although Kathy says more still are needed.

“They’re serving over 200 survivors alone in northeast Wisconsin. That’s the numbers we’d been looking at for the statewide warm line. We thought we’d get a couple hundred calls a year for the entire state.”

Nick Ross and Kathy opened the office in December of 2019. It was a hectic time. Kathy recalls working from 6:00 a.m. to 10:00 p.m. every day, frequently traveling the state.

“I didn’t have rest, I didn’t have any kind of life. I was all about the advocacy. I trained Nick to be the same way. We’d just be go-go-go. And then the pandemic hit.”

The way they worked had to change. But calls to the warm line, she says, quadrupled. They were hearing from young people sheltering in place with abusive, often homophobic and transphobic parents. It wasn’t just high schoolers, either, but also included droves of college students who’d been forced to return home and often go back into the closet.

At the same time, another influx of LGBTQ youth needing support came when Goodwill shut down its 25-year-old LGBTQ Partnership and fired the staff. The combination meant that the Appleton D&R staff were already underwater to meet all the needs of the community. Kathy scrambled to do some budget amendments and drummed up support from groups like the Community Foundation for the Fox Valley Region. Those efforts paid off. The money meant they were able to hire the staff who’d been fired from the Goodwill program. Reiko Ramos began as a part-time advocate but quickly moved to full-time, and has since stepped into the role that Kathy left, as the Anti-Violence Program Director.

The enormous need for youth services also inspired Kathy and her fellow advocates Reiko and Nick to launch Room to Be Youth, programming aimed specifically at supporting the influx of LGBTQ young people in need. Since then, the program has grown to include support groups for both high school- and middle school-aged young people, plus a new QTBIPOC group coming this fall, as well as the overall Room to Be Safe Thursday night group aimed at adults.

Meanwhile, as the COVID-19 pandemic was unfolding, a different debilitating illness struck Kathy down. She was diagnosed with Influenza B and, because her other autoimmune diseases kicked into overdrive, she spent five months in bed. Working.

“I worked in my bed,” she says. “The flu kicked my MS into something far more serious. I kind of hobbled along for the rest of that year.”

The effects of that illness stayed with her for a long time. In 2021, just when the Appleton office was preparing to re-open, Kathy began to have breathing issues that landed her in the emergency room. She tried to switch to part-time work, but says that she was back up to 40-plus hour weeks after just a month.

Other MS symptoms began to get more serious during that time, and the treatments weren’t sustainable. Her doctor told her the MS had progressed from what’s called a relapsing/remitting form of the disease and moved into secondary progressive. It means, she says, “you don’t get better.” While she’s still able to walk, sometimes with a cane and sometimes without, she’s had to do a major reassessment of how much work and stress she could afford to put on her body.

Her doctor recommended she take six weeks off, something she’d never done in her life. But that time off proved crucial. Kathy learned to meditate and be in-the-moment. She felt better, but knew when she went back to work that she still wasn’t well.

“My disability was overtaking my body,” Kathy says. “Cognitively I wasn’t as sharp. I was missing math stuff that I would have never missed on a grant before.” She knew almost immediately that she needed to quit.

Challenges of Collaboration and Succession

Having time to rest has meant time to reflect as well. Initially, Kathy worried that she wouldn’t know how to define herself if she was no longer an advocate, no longer working long hours to support survivors and push better policy and protest.

“But it was really time,” she says now. “And my body reacted almost immediately.” She says her physical health actually got worse when she stepped down. Her body is “just finally letting go,” she thinks. Things have leveled out a little since, but it’s still early days. In typical Kathy fashion, she’s determined to be as good at resting as she was at working.

Gardening, meditating, resting, and being a parent and grandparent have largely become the focus of her days. Still, she can’t help but stay tuned into the movement, lending what support she can in a new, more behind-the-scenes capacity.

“Where I’m at now, my entire life has been with a sword in my hand. I couldn’t lay the sword down if I was in the workplace. I tried. Part of me leaving was acknowledging that I need to lay the sword down and rest.”

Local queer, trans, and BIPOC leaders still find their way to Kathy’s house for conversation, advice, and support. “That I have some energy for, but I don’t have energy for much more. That feels much calmer to me, to be able to be that person, let me get you a cup of tea, sit down, let’s talk about, how can I support you?”

Kathy turns to the notion of succession, noting that she believes it’s time for a new generation to take the lead. A presentation by the poet and activist adrienne marie brown especially caught her attention.

“She talked about how she had to step down from activism for a while and how it allowed other people to step up,” Kathy relates. “What I know, in BIPOC and queer and trans orgs, is we better be thinking about succession because this work will burn you the fuck out. It will lay you flat. So if you aren’t mentoring, if you’re too self-absorbed in this work…in the last few years I’ve really put intentional focus on training up the next generation to lead the anti-violence movement.”

That becomes especially pertinent when she reflects on the more difficult things she’s learned and encountered on her journey. Specifically, racism and white supremacy within the DVSA community, which is still all-too prevalent. It is another part of the equation that Kathy says led to her own burnout.

“The other thing I was dealing with, and this is the heartbreaking thing—because of my whiteness, my role has always been to challenge white people,” Kathy says. “My privilege means that I should do that. But at the same time it’s the most exhausting shit to be challenging white people. When I got deep in the director’s circle of the DVSA movement, the racism of white women in this movement surprised even me. I feel naive even today saying I did not know, I did not really witness it as harshly as I did until the last couple of years.”

She cites several examples of how this has played out in front of her eyes. Her perceived whiteness has often meant that other white people will say and do things in front of her that they might not do in front of others. But some of it has also happened right out in the open and been aimed particularly at BIPOC people who take over as directors and/or found and lead their own, culturally specific organizations.

“People would say, ‘Why are we talking about race, what does this have to do with domestic violence? Why don’t we just get back to DV?’” Kathy says. “It was so frustrating. Most of my job in the past two years was addressing racism with these white directors and checking them and challenging them, trying to be that aspiring ally to Black and brown folks. And to remind them of how all violence is linked to racism and oppression.”

Kathy acknowledges several times during the conversation that her own anti-racism journey has been long and filled with mistakes and missteps. She has enormous patience and grace for people who make a good-faith effort to acknowledge where they mess up and try to do better. “We’re all swimming in this pool of white supremacy,” she adds.

But there was a flip side to the role she took on, and it also took a toll.

“I deal with and acknowledge my privilege, and yet racism has also impacted me directly,” she says. “I was aligned with the BIPOC directors, they asked me to be in those meetings, and sometimes it was to be that voice to go deal with the white people who were out of hand. That has been my role for a long time. I take it seriously, but it also worn me down because there’s this other part of my identity that exists. My Mexican identity. I’m still hearing anti-immigrant, racist shit, you know?”

Kathy notes that it’s the most disappointing to hear and see racism coming from white people who consider themselves to be feminists. Part of the issue is also wrapped up in a scarcity mindset, she says, that meant when funding started going to a more diverse array of organizations, especially those that are by and for Black and brown folks. “Some white women started losing their shit and viewing BIPOC orgs as competitors rather than collaborators.”

There are, she notes, many great allies within the community. Many of them came from causing harm and getting called in, getting “checked and checked again” until they learned and grew and started doing the work. There are also many more Black and brown leaders coming up in the movement, something that’s needed and overdue but still met with backlash, Kathy says.

I know my whiteness gets me in the door and they can hear it from me better,” Kathy says. “That pissed me off, that a Black woman can’t say things in the same way I say them without pushback. It opened my eyes. And with my health, the stress of it just tanked me.”

The stress wasn’t limited to racism within the movement, either. There have been far too many times that people Kathy worked with and saw as friends and allies were revealed to have caused enormous harm and then refused to take accountability for it. Those have been some of the most difficult and heartbreaking episodes in her life, she says.

“One of my biggest pains in the movement is that I have been visibly friends with men and non-binary folks who have caused sexual harm to others,” Kathy says. “As their friend, I’ve tried to help—you did this shitty thing, and I’m a sexual assault advocate, I wanna help you. But there has never been a man who has accepted my help. I’ve had six friends that I’ve lost who’ve caused deep harm to mostly women, yet don’t want to own any of it. That’s where I have to cut them out of my life.”

She calls it one of her biggest regrets in life to have been “so publicly aligned with somebody who has caused harm, and I didn’t see the red flags early on.” Kathy acknowledges that such thinking puts the onus of someone else’s behavior on her, but it still feels heavy and complicated.

“It breaks my heart to know that survivors saw me close to anybody that was causing harm that I didn’t know about,” she adds. “Once I knew about it, I still wanted to help those individuals not cause harm anymore but they never wanted that help.”

And there is a real need for support for people who have caused harm who do want to make amends and change, Kathy notes. In progressive movements, there’s often too much willingness to tear people apart and casting them out for even much smaller missteps and harms. Kathy admits to having gone through many phases herself where she was too rooted in hardness and judgment instead of grace. These days, she finds there’s a healthier middle ground that provides a way forward.

“For me, I’m gonna give you grace if you come to me and say, ‘Man, I fucked up.’ Because you can recover from that, but you have to have accountability. And accountability has to be survivor-driven. It might mean you can’t recover with that person that you hurt. It’s not their job. Like if you did something racist, it’s not that Black person’s job to forgive you. But it’s your job to learn and change and move on and grow from it. I have grace for that. I don’t have grace for people who go, ‘That’s not racist, no I’m not being racist.’ I get to the point of, ‘I am done, I’m cutting you out.’ It really comes down to, are you willing to own your shit?” Kathy adds. “And I will sit with you in the shit if you’re willing to do the work.”

Embracing a Legacy Mindset

Change is inevitable. Kathy is doing her best to lean into this new, less hectic stage of her life, which she happily refers to as her “crone phase.” She acknowledges that, now more than ever, she doesn’t know how many years she has left and wants to make the most of them in a way that’s more inwardly focused on her own healing and time with family.

That doesn’t come without challenges, of course. She wouldn’t be who she is if it was easy for Kathy to sit still for very long.

“I still feel guilty every time I spend half a day in bed,” she says. But the MS doesn’t give her much choice, and so Kathy is learning to be as okay with that as she can be. It’s meant finding ways to fend off feeling isolated, to maintain friendships with people who are still actively in the movement despite having less in common and less time together. Her friend circle, she says, has gotten smaller but tighter. She’s gone from being a social butterfly, someone who loved working 60–70 hour weeks, to someone who is learning how to embrace rest and stillness.

Kathy enjoys becoming a queer elder, which she laughs and says several young people have now called her just that.

“Other people at 56 do not identify as an elder, but I do,” she says. “I strongly identify as a mother and a grandmother, that’s part of my identity. In the movement I feel like I’m mother/grandmother, too. There’s a lot of responsibility that comes with that, including knowing when it’s time to step back so others can step forward.”

She refers to herself as “legacy minded,” noting that she’s had just about every experience there is in DVSA work and wants to pass on any wisdom or lessons learned to the next bunch of advocates for the future. It’s a way to stay involved while still honoring this newer, slower pace and phase of her life.

“It’s this interesting place to be such a dominant, hard-nosed figure…but also have this fragility. So I’m trying to lean into the fragility of life a little bit more. That means holding my relationships more fragile, holding my life a little more fragile.”

In a life filled with lessons about privilege, Kathy recognizes that, while she still has it in certain areas, she’s lost it in others where she once had it. Her physical abilities, for one. But she sees it as an important lesson, one that we all eventually have to learn.

And there are so many things to look forward to—new ways of doing and thinking about things. Kathy is particularly interested in how she can help others embrace the softness she’s been learning to welcome into her life. It’s something she’s worked on a lot in therapy over the past several years, to the point that she says even her bedding and her sweaters are all extra soft.

“The next direction for me might be to help warrior advocates learn how to soften,” she says. She wants to do for others what her own mentors did for her in helping her find her confidence and her footing in the work. Once again, she highlights her past boss and mentor Beth Schnorr.

“I remember being terrified the first time I had to present when I was leading community education with Harbor House,” Kathy says. “But Beth came to my first presentation, and she was my biggest cheerleader. Now I want to be that person in the audience saying ‘yes, you’re doing great.’ I want to make room and make sure Reiko, Nick, Keira, Passion, and Andrew—everybody at D&R—are able to have that. Whatever I can do to support them and be their biggest cheerleader.”

Right this minute, sitting in her kitchen with a cuddly, soft Yorkie curled up on the floor next to her, all Kathy knows for sure is that she’s content to “heal a little bit and rest.”

And while there are things that are constantly happening in the community that call to her to get involved, she reminds herself that she’s done so much and that it’s time, at last, to watch and cheer on new people as they take the baton and run.

Emily Mills is the former editor of and a current board member for Our Lives magazine. She is a writer, musician, photographer, and nature lover currently working for a non-profit environmental organization where she sometimes gets to help set (planned) fires. Emily lives in Madison with her partners and two small dogs.

0 Comments