Madison’s history with LGBTQ Pride is a storied and evolving series of events. As we commemorate a landmark anniversary in the LGBTQ movement, let’s look back at the ways Madison has gathered together in pride during the summer months over the last five decades.

In late October 1969, just four months after the Stonewall Rebellion spurred the ongoing movement for LGBTQ rights, several men gathered at the St. Francis House (the Episcopal student center at 1000 University Avenue) to form what would become the first gay liberation organization in Wisconsin—the Madison Alliance for Homosexual Equality (MAHE). As the group continued meeting into spring 1970, members began to be more “out” in the Madison community, taking on a more educational and political agenda.

MAHE would go on to achieve many queer firsts in the state that year, including the first appearance of openly LGBTQ individuals on television and radio, the first public LGBTQ dance, and the first public LGBTQ protest.

On May 1, 1970, MAHE held a day-long teach-in at the UW Memorial Union that featured educational panels, a screening of the early classic lesbian film Mädchen in Uniform, and ending with a dance in the cafeteria. It was the first public educational and celebratory queer event in the state, held before even the first Christopher Street Liberation Day March in New York (the commemoration of the Stonewall Rebellion that would become an annual tradition celebrated internationally). The MAHE May Day Conference was a success. It would become an ongoing fete in Madison during the decade of the 1970s, picked up by succeeding local political groups like the Madison Gay Liberation Front, Madison Gay Activist Alliance, and the Madison Committee for Gay Rights.

Early community efforts

In December 1972, with the drinking age newly lowered from 21 to 18, Madison native Rodney Scheel opened the first bar owned and operated by an openly LGBTQ person in Madison’s history, The Back Door, located at 46 N. Park St. Customers entered through the back door of the building, went down the stairs to the bar in the basement, and were greeted at the bottom of the stairs by a life-size mural of Dorothy and Toto with the quote, “Toto, I have a feeling we’re not in Kansas anymore.” Up a set of inner stairs was the city’s first LGBTQ dance floor.

The Back Door quickly became a community institution. As a thank-you to patrons, Scheel held a community picnic on June 3, 1973 in Brittingham Park, which was walking distance from the bar. The event was such a hit that the Back Door patron appreciation picnic would become an annual Madison summer community celebration for the next three decades.

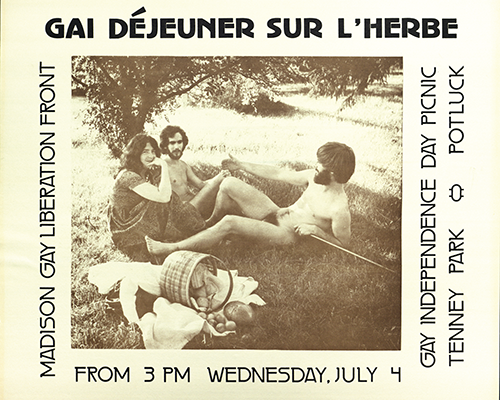

During this period, the political LGBTQ organizations in town chose the July 4 holiday as a popular day to hold summer community picnics. In 1973, the Madison Gay Liberation Front sponsored a picnic in Tenney Park on July 4. Linda Newman, who graced that year’s poster, remembers, “There were lots of people, lots of sunshine, and lots of good friends.” Madison Gay Activist Alliance, a successor organization, sponsored a community picnic the following July 4, 1974 at Tenney Park as well.

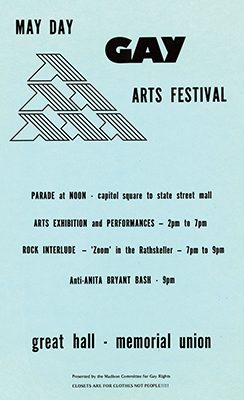

May Day Conferences continued with a 1977 May Day Gay Arts Festival at the Great Hall of the Memorial Union, sponsored by the Madison Committee for Gay Rights. The event began with a parade at Noon from the Capitol Square down to Library Mall, followed by exhibitions, and ending with a 600-person-strong May Day Rally against Anita Bryant and her nationwide “Save the Children” crusade against homosexuals. Both Mayor Paul Soglin and State Representative David Clarenbach addressed the crowd.

A MAGIC era

The following year during the 1978 May Day conference, Madison’s sexual orientation non-discrimination ordinance was under threat of repeal by a referendum urged by Reverend Wayne Dillabaugh, a conservative evangelist, part of the national gay rights repeal campaign led by Bryant. At the Gay Rites of Spring Dance on May 1, 1978 in the Great Hall of the Memorial Union, Madison LGBTQ bar owners announced a group, M.A.G.I.C., Madison Area Gay Interim Committee, formed to fight the proposed referendum.

Bar owners collaborated in sponsoring the Back Door picnic, renamed M.A.G.I.C. picnic, to use the profits to fund local political action. The referendum push fizzled, and the M.A.G.I.C. picnic continued for two decades as a fundraiser for local queer causes, becoming a regional celebration, as local LGBTQ organizations planned events to coincide with the annual picnic.

The M.A.G.I.C. Picnic settled into being held the third Saturday of July to avoid conflicts with other regional Pride events in Chicago and Milwaukee. The picnic featured information tables from local organizations, vendor booths, dancing in the Brittingham shelter pavilion, a beer tent, performers, a Saturday night dinner, and an array of games from water-balloon tosses to the purse throw. During the “drag race” competitors outfitted themselves in drag attire throughout various stops along a course. Madison’s annual Gay Volleyball Tournament also scheduled itself in coordination with the picnic. Beginning in the 1980s, bars from Chicago and Milwaukee even sent busses in for “M.A.G.I.C. Picnic Get-Aways to Madison.”

The efforts in planning the M.A.G.I.C. Picnics, which would continue for the next 20 years, were staffed and paid for by the local LGBTQ bars. Leadership, staff time, and resources in planning the event continued to be provided by Rodney Scheel and the staff at The Back Door, and later the Hotel Washington.

In 1987 a group of local activists, including Pam Jacobson, Tim O’Brien, and Richard Kilmer, began working to organize a local political march, in contrast to the community celebration that was the M.A.G.I.C. Picnic. “We need to become a more visible political force in Madison and in the state,” said O’Brien at the time. Inspired by the National Gay and Lesbian March on Washington in October 1987, they created The Madison Pride March Committee which named itself GALVAnize (Gay and Lesbian Visibility Alliance). They held a Madison Gay Pride Rally and March on May 6, 1989. Over 7,500 people attended the rally. The Rally was accompanied by an ambitious and well-attended week-long series of events, including a photography exhibit, concerts, workshops, and an exhibition of panels from the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt.

Two years later a new group of activists organized a successful second march under the GALVAnize name on October 5, 1991 which drew over 5,000 people. Again, the amount of effort involved in producing the large event was difficult to sustain for the all-volunteer staff, and this GALVAnize group disbanded after the event.

Three years later GALVAnize was revived by Ben Doran, Maria Hansen, Steve Starkey, and Alan Strozak, and held marches in 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, and 1998. The 1996 rally was held in the aftermath of the fire that destroyed The Hotel Washington complex of LGBTQ establishments, and after a Madison firefighter passing out anti-gay literature at a city fire station. The community responded. About 2,500 people marched around the Capitol Square and the crowd swelled to 5,000 for the post-march rally in Library Mall. Alan Strozak was emceeing the rally in Library Mall and recalls, “It was insanely exhilarating to watch a sea of people marching directly toward us!” The 1997 March occurred in the wake of the federal Defense of Marriage Act and brought 1,500 people to the Capitol who then marched to join revelers at the Magic Picnic at Brittingham Park. “This is the one day of the year we all get together and celebrate who we are,” Linda Lenzke said at the time. “This is sort of like a family reunion every year.”

Struggles and support

In 1999 The Magic Picnic and GALVAnize Pride March merged into one organization called Madison Pride. It was a community organization that included participation from many of the local LGBTQ bars: Ray’s, Club 5, Cheri’s Back East, and others. They held the picnic and the parade all on the same weekend from 1997 through 2008. Other local organizations went back to organizing events around the weekend: Friday nights were OutReach’s annual dinner followed by the Ten Percent Society Dances in the UW Memorial Union, the picnic on Saturday, UW–Madison GLBT Alumni breakfast on Sunday morning, and the Pride Parade early Sunday afternoon, which proceeded from the Capitol down West Washington Avenue to the festival in Brittingham Park.

In 2008 the treasurer of Madison Pride, Scott Toomey, swindled the group, leaving the group with $4 in its checking account and over $8,000 in unpaid bills from the previous year. The event, which had been drawing 6,000 people over the course of the weekend with the Picnic hosting 15 performers and 50 vendors, was drastically scaled back. A Sunday rally with fewer than 400 people was held at the Capitol and one musical act at Brittingham Park followed. Many in the community were left sad and dismayed.

Three groups stepped in to help fill a felt void created by the demise of Madison Pride: Two local bars, and one group of community volunteers. Plan B nightclub owners Rico Sabatini and Corey Gresen, decided in 2010 to offer a free LGBTQ Pride season music festival in the club’s parking lot and spilling onto Willy Street. Fruit Fest featured a charity 5K run/walk, and day-long music festival with a mix of local and national LGBTQ performers. That event continues to this day, now under the auspices of the renamed Prism Dance Club (co-owned by Sabatini and Apollo Marquez). Also in 2010, WOOFS bar owners Dino Maniaci and Jason Hoke created a block party outside of the club on the 100 block of King Street as a celebration of Madison’s LGBTQ community and its supporters. This free event allowed attendees to gather in the street to enjoy music, beer, and food. It also hosts a charity component, raising funds for local, community based organizations such as StageQ, ARCW, OutReach, and most recently, GSAFE.

Around the same time, a group of volunteers formed Wisconsin Capitol Pride in 2009 to plan a new Pride event for Madison. Wisconsin Capitol Pride hosted a weekend of events featuring local and national LGBTQ performers on Willow Island at the Alliant Energy Center. The venue necessitated a parking fee and a separate entrance fee to the grounds. A parade was held on Sunday around the Capitol Square, after which attendees could move to Alliant Energy Center for the remainder of the festivities. These festivals continued until 2013 when Wisconsin Capitol Pride unexpectedly cancelled Pride just two weeks before the event was to be held and disbanded. Maintaining volunteer support to produce a large-scale weekend series of events had proved difficult to sustain.

Current efforts, continued challenges

Following the cancellation of Pride in 2013, individuals and organizations in the LGBTQ community asked OutReach to organize the parade. OutReach agreed to work with a coalition of groups (WOOFs, Fair Wisconsin, PFLAG, Our Lives, and others) to host a parade, planned around a weekend of other events (which have included WOOF’s Block Party, Willma’s Fund Pride Show, Hot Summer Gays, and Our Lives’ QTPoC Pride Brunch).

OutReach offered staff time and resources to handle the detail work of raising funds; negotiating with the Madison City Street Use Staff Commission for dates, routes, and required police presence; organizing the contingents for the parade; managing vendor permits and non-profit tables; coordinating the volunteers who ran the event; and bringing together the post-parade rally in collaboration with other LGBTQ organizations.

These efforts resulted in a 2014 Pride parade route that went up Williamson Street to the Capitol Square, attended by about 1500 people. Many community members were glad to have a LGBTQ parade again in Madison. The 2015, 2016, and 2017 OutReach Pride Parades grew in attendance each year. The route up State Street to the Square was popular, and a rally was held afterward at the Capitol. Many groups sponsored the event and contingents grew from 60 to 90 in number. The crowd estimate for the 2017 march was 5,000.

Partly in response to national events in 2017, a loose-knit group of activists who eventually called themselves the Community Pride Coalition engaged the community in conversations about the appropriateness of uniformed and armed police officers marching in the Pride parade. Pride parades started in 1970 as a commemoration of a rebellion against police harassment of members of the LGBTQ community. Many in our community today feel unsafe with police officers marching while armed and in uniform.

Community conversations ensued about the need to take a stance against current police mistreatment of the LGBTQ community, particularly people of color. Community Pride Coalition worked toward ending the participation of armed, uniformed police marching in Madison Pride 2018, requesting participation unarmed and in civilian clothes. OutReach, Community Pride Coalition and the Madison Police Department met to seek a compromise, but one could not be reached. Eventually OutReach withdrew the application for the Madison Police Department to march. This proved controversial, with some in the community pleased and others very upset at the decision, which received considerable media attention. Nevertheless, the ensuing 2018 OutReach Pride Parade was a success, boasting the largest amount of contingents yet, and crowds well over 5,000.

In 2019 OutReach attempted to host a parade, but were presented with new challenges by the City of Madison Street Use Commission. After meetings regarding changes to City policies regarding events in the downtown area and police coverage requirements, OutReach decided to return this year’s event to community roots—an OutReach Magic Festival. This celebration will offer an opportunity to socialize together in community at Warner Park on Sunday, August 18 from 1:00 to 6:00 p.m. Activities at the park will include the QTPoC Pride Social, a mainstage with live entertainment, booths from local community organizations, merchandise vendors, food vendors, a beer tent, and games. Warner Park offers free parking, no entrance fee, and attendees can bring food (but no alcohol) into the park.

In reflecting on the preparations for this year’s event, Steve Starkey commented, “Pride events in Madison over the decades have helped to build connections and relationships in the LGBTQ communities. They’ve also increased the LGBTQ visibility to the general population. Pride events are a lot of work to organize, and are worth it because of the progress we build through them.”

Thanks to Emily Mills and Ron McCrea for their editorial assistance. Thanks to Steve Starkey for providing background for this article.

0 Comments